How Did These Runners Get So Good?

South Africa’s richest running talent comes from its poorest communities. This is the story of how the country’s finest Comrades runners are grown.

The sun dips behind the Sentinel, the peak that marks the western end of the mouth of Hout Bay, and in its wake throws ochre, scarlet and violet across a darkening sky. I’m running up Chapman’s Peak Drive when I’m passed by two lightweight guys, whose slender limbs turn over in a beautiful, economical running style.

I watch as they climb the hill, effortlessly, almost poetically. My admiration for this is enough to take my mind off the fact that in comparison, I myself am finding the same elevation extremely labour intensive.

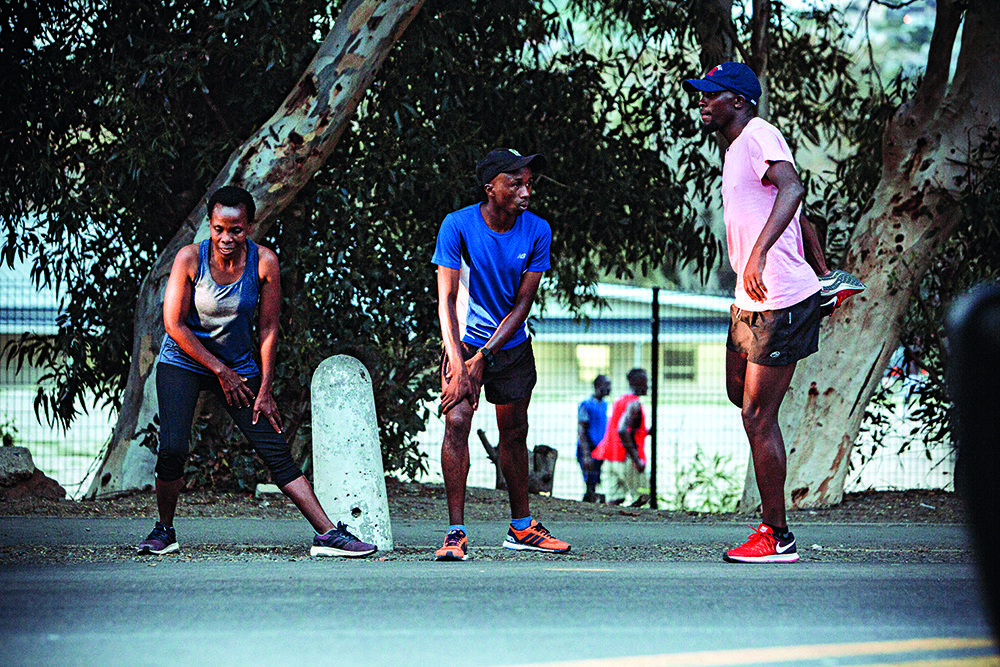

I find them relaxing at the summit, and stop for a chat. They’re 33-year-old Anda Lubelwana and 31-year-old Phumlani Nxusani from Imizamo Yethu (IY), a township in Hout Bay. It appears that they and one of the other runners from IY, 32-year-old Admire Rushika, can run a marathon in under 2hr30 – which should mean they’re capable of finishing in the top 10 at Comrades, if not winning it.

Other success stories from IY include those of Nomvuyo Spamla and Nomawethu Nika, two 43-year-old friends who finished their first Comrades in 2018.

There’s talent in IY, and these runners work hard. So the basics are certainly there. But at the same time, I’m aware of the harsh reality that athletes from low-income communities face when it comes to affording race entries, running shoes and good nutrition.

Who’s helping them?

Humble Beginnings

All of the runners I meet were born into large families in rural farming communities.

After her mother left her, Nika became one of 14 grandchildren living in one house in Tarkastad, a semi-urban settlement in the Eastern Cape. She remembers her grandfather going out to the fields to milk cows and collect wood. Rushika grew up in Zimbabwe’s Hurungwe Province, where tobacco, maize and soya beans are grown.

There used to be a competition in Anda Lubelwana’s village. He and the other children would run, and whoever covered a certain distance first would be given mielies – the first time he won this prize was the first time Lubelwana realised he was good at running.

At the time, this was his only experience of running. Many in the townships do not have access to the information on the internet about races, training programmes and advice. As with many of South Africa’s talented runners, his circumstances had effectively kept him in the dark.

Noma Nika was fortunate. Her grandmother treated her well, and she grew up to be a confident woman. But Nomvuyo Spamla wasn’t so lucky; her eight siblings bullied her for being shy. Children look to their immediate family for encouragement, love and support, and if they don’t receive this affirmation, their self-belief suffers.

“I found it difficult to talk openly about myself, and I didn’t know what I wanted,” Spamla reveals.

She dropped out of school when she was 15 years old. Her parents separated, and her mother, who is uneducated, decided they would move to Cape Town in 1990. Spamla had to look for a job to support her family. Now, she works as a house manager for a Cape Town-based company.

Nika didn’t pass matric either. She too came to Cape Town looking for work, in 1999 – and by then, she had two children to support. She found work as a domestic worker, and enjoyed looking after children. She found her calling: now, she works for a charitable organisation called Shine Literacy, which works with local and international volunteers to help children with reading and writing.

The Why

Though they come from similar backgrounds, these athletes all took up running for different reasons.

Noma Nika is well-travelled: she was the first black South African woman to climb the seven summits of the world. But it was time for a new challenge.

She remembers watching the Two Oceans participants pass IY. Members of her community were out in their droves, cheering and shouting words of encouragement. It was clear they were passionate about the race; and yet, none of them were taking part in it.

“I wanted to be one of the runners inspiring my local community,” she says.

But many race-entry systems in South Africa are set up in a way that discriminates against the uneducated and those without easy access to the internet.

Nomvuyo Spamla had dreamed of racing the Comrades ever since seeing the race on television when she was 16. But she hadn’t the confidence to even start running – until she had a health scare, in 2016.

Spamla remembers it was early in the morning, before 6am, and the weather was cold. She was waiting for a taxi in Cape Town city centre when she began to experience severe stomach cramps. Concerned, she informed her boss she wasn’t coming in to work that day.

“My boss asked me if I’d ever had a Pap smear,” Spamla recalls. “After I explained I hadn’t, she took me to Christiaan Barnard Hospital.”

A gynaecologist told her initial tests showed ‘unknown cells’, which were a possible indication of cancer of the womb. Thankfully, further tests ruled this out, and doctors later believed Spamla’s pain had been caused by a minor issue in her colon. Although her pain eventually subsided, she had gained weight. She was advised to eat healthily, and exercise.

“I couldn’t follow a strict diet because I didn’t have the money to buy expensive health food,” Spamla says. “We are what we have – I ate fruit, vegetables and lean protein when I could. I also started running twice a week.”

But when they discovered she had started running, some of the residents of IY accused her of wanting to be ‘white’. Admire Rushika was met with the same reaction back in 2010, when they discovered he was running the 5km stretch from Llandudno Construction, where he worked, to his home. Running was seen as a sport only the rich could afford to do.

And yet, none of these runners were deterred – especially Rushika, and Anda Lubelwana. When you come from a township, the prize money for winning Comrades could literally change your life.

When Lubelwana moved to IY from the Eastern Cape, he struggled to find a job, because of his lack of education – and there was a language barrier. Now he has a job pushing trolleys at a local supermarket; but that’s doesn’t bring in enough for him to afford decent nutrition and running shoes.

The How

When marathon runner and mountaineer Evelina Tshabalala [third lady at the Two Oceans Ultra in 1993] still lived in Hout Bay, she used to bring runners from IY to the Hout Bay Harriers weekly 5km time trial. Admire Rushika was one of them. He’d never run a race before, and didn’t even own a pair of running shoes; yet he won it at his first attempt, in 2010.

“When we’d run past IY in Hout Bay colours at Two Oceans, we’d get the most incredible support,” says Graham Botha, former Hout Bay Harriers Chairman. “And as excited as they were, I imagined they would be even more excited if there were people from IY among us.

“We had these talented guys, running fast times at our time trial – and they all wanted to do races, which was something we had to address. But it was never about finding super-talented runners to make the club famous; it was more a case of getting a mix of runners that would reflect our community.”

It was time to bridge the gap.

The Harriers decided to set up a development programme, managed by some of its committee members and now run by Botha. An advertisement was placed in a local newspaper calling for new runners to sign up for a 10-week beginners’ training programme, hosted by the club.

Around 50 people responded, and each was charged a fee of R300. The proceeds were used to help runners from IY with race entries, transport to races, and running kit. In addition, more affluent runners donated their old running gear.

But the real game-changer was an annual half marathon, the Chappies Challenge. The entry fees from this race alone gave the Harriers such a boost, they could afford to send their development runners to Comrades – something they’d never been able to do before.

“Last year, we weren’t given permission to use Chapman’s Peak Drive and had to cancel our race, which has had a serious impact on our development programme,” says former Harriers chairman and current committee member Gregson Lubbe. “This year, we’re only sending two runners to Comrades, and even that’s a stretch.”

Noma Nika was one of the runners who’d dreamed of running Comrades, and the Harriers made it happen. She remembers the first time she ran with the club – on a 5km route, from the old clubhouse at the Yacht Club to the Hout Bay Checkers and back. Before that, she’d been running alone on Hout Bay’s leafy Valley Road. The Harriers were keen to teach her the basics of running, from what to eat to how long to run for in training. From such humble beginnings, she eventually made it to Comrades in 2017.

“But I didn’t make the cut-off at Comrades. I had just seven kays to go,” she says. “A guy from Durban gave me his medal, on condition that I would earn my own the following year, and give his medal back to him.”

In the same year, Nika met Nomvuyo Spamla, who waited for her at the finish line of the Cape Town Marathon.

“I knew Noma was the only black woman living in IY who ran for the Harriers,” Spamla says. “I had recently joined the club, having been encouraged to do so by Francis, one of the members I’d met running up Chappies. In fact, the other members sometimes got me and Noma mixed up!”

The pair formed a close friendship: Spamla had dreamed of running Comrades since age 16, and Nika had unfinished business. They began training for Comrades together – anything between 5km and 13km on weekdays, and a long run of up to 46km at the weekend.

“It was never about making the club famous – it was more a case of getting a mix of runners that would reflect our community.”

Nika had the confidence to boost Spamla’s self-belief at times when she felt scared. And because Spamla was a faster runner (she finished Comrades in an impressive time of 9:46.34), Nika had to work that little bit harder in preparation for her second attempt at finishing the race.

“I remember panicking on race day, because I hadn’t been able to finish the year before,” Nika recalls.

“I was looking for a portaloo, but the road was closed and I had to jump over a fence to get to it.

“I never felt tired though. My legs felt fine. But I was struggling to breathe.

“I saw Graham at 13 kilometres to go. He said to me, ‘Noma, you’re going to hate yourself if you don’t finish. You have two hours and seven minutes left – walk if you have to!’

“Then, at 10km to go, there were these guys who were sitting at the side of the road drinking. I’d never touched a drop of alcohol in my life, but I remembered something my grandfather used to say about brandy being good for treating respiratory symptoms when you have the flu.

“So I asked them what they were drinking. Whisky, they replied. I told them I wanted a tot – and to make it a strong one. And you know what, it actually worked! I ran the last 10km.

“Crossing the finish line, Vuyo and I shared happiness we couldn’t share with anyone else. Even if we told other people how we felt, they wouldn’t understand.”

New heights

While the pack runs hosted by the Harriers aren’t fast enough for guys who can run a marathon in under 2hr30, the club gave Admire Rushika and Anda Lubelwana the opportunity to showcase their talent to elite running clubs that could help them with structured training programmes.

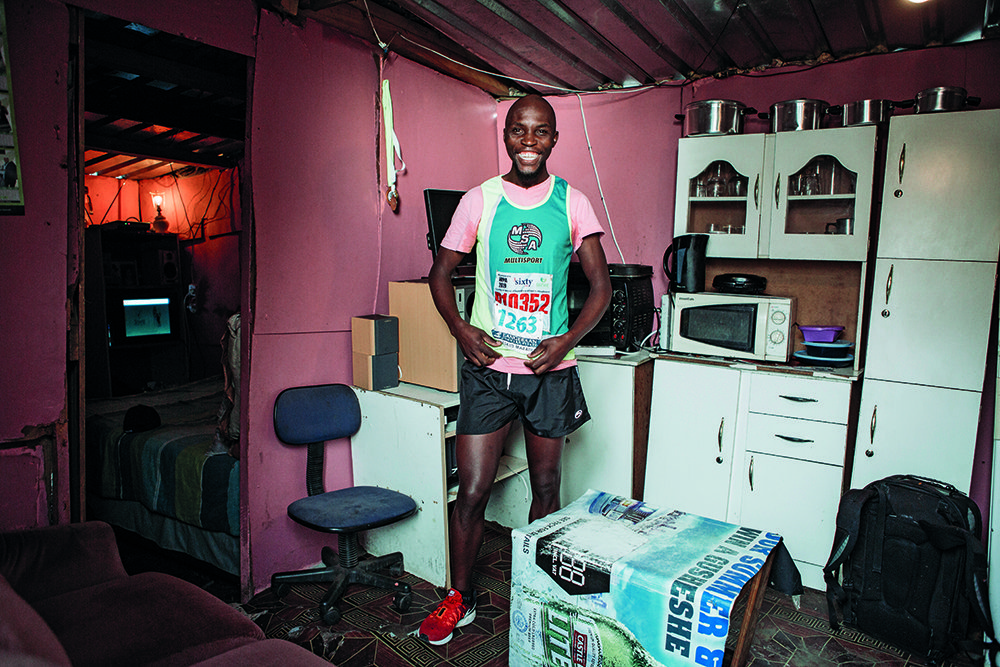

Rushika’s proudest racing achievement is winning the Prison to Prison Marathon (his time: 2:25.17), which was when he was discovered by Nedbank Running Club. Lubelwana was later signed by KPMG (now Murray & Roberts Running Club).

“I used to live in Hout Bay, and often saw Anda running there,” says trail-running star and fellow Murray & Roberts athlete Nic de Beer. “I asked some of the locals what he did for a living, and where he lived. Anda and I met for coffee, and I told him we wanted him to join us. We offered to pay for his travel, accommodation and entries to races.”

In 2013, Lubelwana started running with Phumlani Nxusani, who also lives in IY and runs for Nedbank Running Club.

“We woke up early and met outside the police station, at the entrance to IY,” Lubelwana recalls. “We started with 400m repeats, which was my first taste of serious training. The following day we ran to Noordhoek via Chapman’s Peak, and the day after that, we ran past the World of Birds on Valley Road and continued onto Victoria Road, all the way to the Twelve Apostles Hotel.”

The pair runs twice a day, six days a week. On a typical Sunday morning, they might run 50km in 3hr55; and on any given weekday afternoon, complete a speed- or hill-training session.

Since Lubelwana has followed a structured training programme under the guidance of his friend, he’s racked up a string of impressive personal bests in the marathon (2:23.13) and the Comrades (6:07.42).

“When he travelled to the Comrades in 2018, it was the first time he’d been on a plane,” De Beer recalls. “I can still picture the excitement on his face.”

As Lubelwana’s story illustrates, South Africa’s richest running talent is alive and well in its poorest communities. If these athletes were nurtured, they could become stars.

And while Nika isn’t going to win any races, her story is equally inspiring. She worries about the issue of those in IY who are overweight, and the serious health implications this has for the people in her community.

But if Nika can motivate just one of her sons to take up running, a change will have begun.

READ MORE ON: inspiring people motivation rural runners township runners