Just Because You Sweat Doesn’t Mean You’re Dehydrated

Prolonged exercise actually liberates water stored within your body.

One of the most vexed questions in sports science these days is how much water weight you can afford to lose before your performance suffers. The standard rule of thumb is that losing 2 percent of your starting weight signals trouble; in contrast, in-competition measurements have found that top athletes generally lose far more. Haile Gebrselassie lost roughly 10 percent of his starting weight during several marathons, including a world-record run, according to one study.

And now, a new study suggests that in ultra-endurance events, you might lose as much as 6 percent of your starting weight without being at all dehydrated. That’s because weight loss doesn’t necessarily correspond to water loss.

Why not? There are several factors to consider.

One is that when you run, you’re burning carbohydrate, fat, and protein to fuel your muscles. And, like the scattered ashes left after a big bonfire, once that fuel is consumed, it’s no longer there. The byproducts of these chemical reactions are carbon dioxide, which you breathe out (thus reducing your weight), and… water, which adds to the fluid in your body that keeps your cells hydrated.

In addition, when your body stores carbohydrate in your muscles and liver, it locks away between 1 and 3 grams of water for every gram of carbohydrate. As you begin burning these carbohydrate stores, the associated water is also released into circulation.

In a 2007 paper, University of Loughborough hydration researcher Ron Maughan and his colleagues estimated that, over the course of a marathon, these factors might allow a runner to lose 1 to 3 percent of her starting weight without any actual reduction in internal hydration status.

This offers a possible clue to the differences observed between lab experiments and actual competition. If you give someone a diuretic or sit them in a hot room to dehydrate them (as is the protocol in many hydration experiments), then 2 percent weight loss is 2 percent dehydration. But in the context of hard exercise, when you’re burning fuel and using up your stored carbohydrates, that’s no longer the case.

In fact, you’d expect the significance of these factors to grow with the duration of the exercise – which is precisely what the new analysis, presented at the Medicine & Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports conference in May, suggests.

RW IN YOUR INBOX: Have the latest news, advice, and inspiration sent to you every day with our Runner’s World Newsletters.

Maughan teamed up with prominent ultra-endurance researcher Martin Hoffman, of the University of California Davis, and hydration researcher Éric Goulet of the University of Sherbrooke, to run the numbers for a typical finisher of the Western States Endurance Run, a 100-mile mountain ultra-marathon. The raw data was based on studies Hoffman and his colleagues have conducted at Western States in the past.

The results found that a “typical” finisher should expect to lose 4.5 to 6.4 percent of starting weight merely to maintain hydration levels. This is a remarkable finding, and argues against aiming to avoid any weight loss, or even trying to limit it to 2 percent.

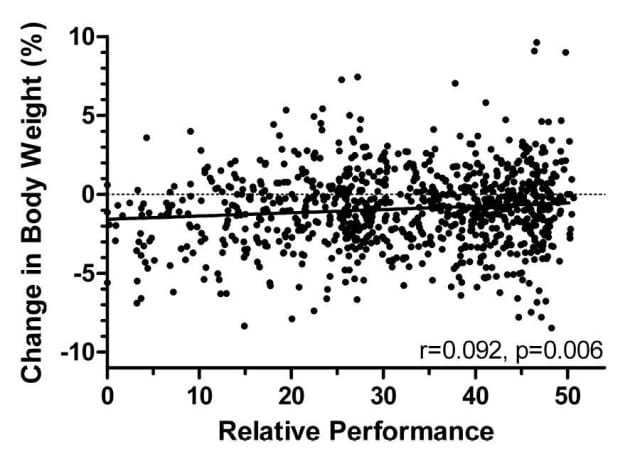

So how does this compare to what ultra-marathoners do in the real world? In a 2013 study in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, Hoffman and his colleagues collected data from five years of observations at Western States (including one year at a neighbouring 100-miler under similar conditions when Western States was canceled due to forest fires). Here’s the range of body weight changes (on the vertical axis), plotted against relative performance (the fastest runners are on the left, the slower ones on the right):

You can see there’s a huge scatter in these 887 data points, ranging from a loss of 8 percent to a gain of 10 percent! Overall, there’s a slight (but statistically significant) trend toward the faster runners losing more weight. There’s certainly no evidence that the slower runners tend to be suffering from dehydration.

Just 19.1 percent of the runners lost more than 3 percent of their starting weight – a remarkable stat, considering the estimate above that 4 to 6 percent loss corresponds to a maintenance of hydration. In contrast, 36.5 percent of the runners gained weight after running for somewhere between 15 and 30 hours.

What does this mean in practical terms? Hoffman directed me to a set of hydration guidelines for ultra-endurance events that he has put together, the gist of which is that you should expect to lose some weight during an ultra run, you should drink when you’re thirsty, you shouldn’t need to supplement with extra sodium, and you should carry enough water between aid stations to allow yourself to drink whenever you’re thirsty.

This advice remains controversial, and no one – including Hoffman – is saying that hydration doesn’t matter. But the idea that you should weigh as much as the end of a run as you do at the beginning seems increasingly flawed, especially if the run is long enough to burn a lot of fuel.