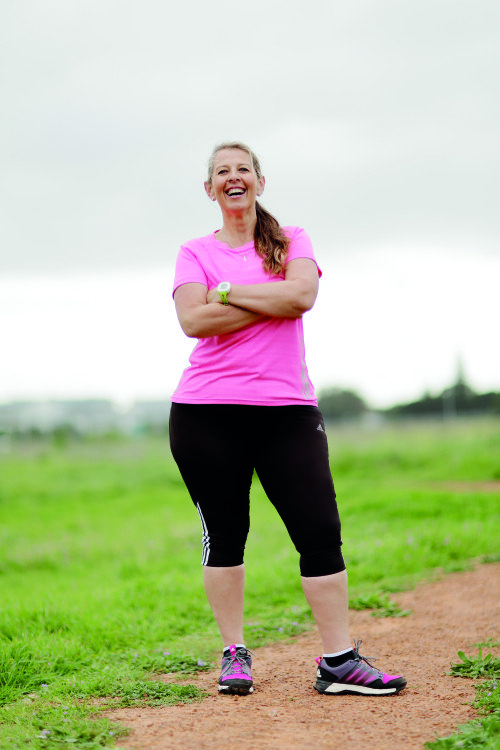

Ultra Runner At 89kg

Is it possible to be overweight, but fit? Healthy and happy, as well as heavy? Michele Bakker provides an inspiring example.

Is it possible to be overweight, but fit? Healthy and happy, as well as heavy? Michele Bakker provides an inspiring example. – By Lisa Nevitt

Since she embarked on a healthy diet and took up running in her 30s, Michele Bakker has lost 45 kilograms. But despite finishing Comrades and the Two Oceans ultra, and with a 2:04 half-marathon PB, she still weighs 89 kilograms – and try as she might to lose weight, she has reached a plateau. “I’ve had everything checked – my cholesterol, lungs, and even my eyesight, are all 100%,” she says. While Bakker is under no illusion that carrying extra weight doesn’t pose risk, she acknowledges the role that diet and exercise have played in offsetting the threat. “The idea that thin equals healthy is challenged at my local parkrun every Saturday,” she says firmly. “There are people of all sizes and shapes who can run.”

The medical profession has contested it, too. “I’d never say that weight doesn’t matter,” says Dr Julia Goedecke, senior specialist scientist at the South African Medical Research Council’s Non-Communicable Disease Research Unit. “There is a massive problem of overweight and obesity in South Africa, and little has been done to address it. But although running doesn’t completely reverse the increased risk associated with Michele’s weight, I agree that it does attenuate it.”

BMI (a measurement of body fat, based on height and weight) determines whether someone is ‘overweight’ or ‘obese’, and is the go-to gauge for ticking the box labelled ‘healthy’. But, according to Goedecke, it’s not your overall weight that’s important, but where you carry fat.

Fat around the abdomen reduces insulin sensitivity and increases the risk for diabetes and heart disease. Diabetes increases your likelihood of suffering a heart attack or stroke.

“That’s why a measure of centralisation of body fat, such as waist circumference, would be a better way to establish risk,” she explains. “The recommendation is to have a waist of less than 80cm for women, and less than 94cm for men.”

But there are many studies to show that regular exercise and a healthy diet have positive health benefits that are independent of weight. For example, running has helped Bakker to improve her insulin sensitivity, which has helped her reduce her risk of diabetes.

“Someone who is thin, but eats unhealthily, smokes and doesn’t exercise is termed ‘metabolically unhealthy’, and typically has less muscle – and more fat, particularly around their organs – than their healthy counterparts,” says Goedecke.

To truly determine whether a person is healthy, factors other than BMI, such as waist circumference, fitness and diet, cannot be dismissed.

Bakker’s Battle

Bakker’s complicated relationship with weight began at school, when she was eight years old. “Our teacher was casting for the role of the portly king in the musical, Old King Cole. All the other girls cheered, ‘Pick Michele: she’s the fattest.’

“Looking back at school photographs, it’s easy to see why I was singled out. All the girls were slim, except for me and maybe one other. But we weren’t obese. Back then, the problem of obesity in junior schools wasn’t common.”

Bakker lived with her parents, father Anthony and late mom Delysia, and her sister Sharon, in Cape Town’s leafy suburb of Rondebosch. She describes her home as “positive, loving and encouraging”.

But Anthony and Delysia were divorced when Bakker was 10. Dad left the family home, and Michele felt an overwhelming sense of rejection. Delysia worked full time, so meals became haphazard affairs. Bakker’s small world splintered, and she leaned on convenience food for support. ‘Slightly chubby’ became ‘overweight’.

But it wasn’t her weight or physical ability that prevented Michele from participating in PE at school – she loved club tennis and netball (and even cadets), and at 18 she taught aerobics at her local church hall, complete with leg warmers and Flashdance soundtrack. It was that at school, she felt insecure and unaccepted.

The air of unacceptability followed her into adulthood. Shopkeepers scoffed: “We have nothing here that will fit you.” Flying on a plane meant requesting an extra-length seat belt.

“My mom, who died last year, suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and numerous other health issues,” says Bakker. “Due to a back and hip replacement, she did virtually no exercise. Seeing her health deteriorate due to her inactivity bothered me.

“At my 30th birthday, weighing 133 kilograms, I was at my heaviest, and wore size 48 pants. Somehow I mustered the confidence to stand on a chair and deliver my birthday speech. The chair survived the ordeal, but I died inside.”

As with most life-changing shifts, Bakker had to hit rock bottom first. At the crossroads, she was faced with a choice: stay that way forever, or do something about it. She did something. First came counselling sessions; then she joined Weight Watchers, a gym, and eventually a running club.

Fitness?

It’s not lack of fitness that’s preventing Bakker from shifting more kilograms – her typical running mileage is between 40 and 50 kilometres a week. She rarely takes walk breaks, and runs between 6:50 and 8:00 mins/km, depending on whether she’s doing speedwork or a long, slow distance.

“Thirty minutes of moderate activity on most days (150 minutes/week) is recommended for health,” advises Goedecke.

Bakker’s father Anthony, who has finished 14 ultras, seven of which were Comrades, influenced the start of her running career, along with two good friends, Bridget van Breda and Debbie Kirsten (wife of former Proteas coach Gary). Bakker joined Celtic Harriers, where she met member Patrick Cox, who offered her coaching that involved daily emails and weekly training programmes. Cox also came to support her on the finishing line at races.

But Bakker acknowledges that love, support and coaching can only go so far. If you want to run, it has to come from you.

During some of their earlier training sessions close to Van Breda’s house in Newlands, Cape Town, Van Breda says Bakker gave up quite easily, realising how much she had to suffer in order to attain the next level of fitness.

“I remember being quite hard on her. But as the challenges got tougher, and we got faster, I witnessed her confidence blossom. The mental shift happened in Wellington at the Safari Half Marathon. I told Michele we had four kays to go, and she opened up the gas.”

When she ran Comrades, Bakker was no longer concerned about her weight, because she’d done all the training and felt mentally strong. Anthony, Sharon and Mark (Bakker’s half-brother) flew up to support her. At the 30km mark, Bakker sat down and cried. She told Sharon that she couldn’t continue. “Get up, and keep going,” her sister ordered.

Sharon reminded Bakker that their mom Delysia would never have given up. “My mother’s strong will to fight through pain until the very end had motivated me on every single training run, and now the pain of giving up seemed to me worse than the pain of pressing on.”

She went on to finish Comrades in 11:55, a result to add to her two Two Oceans ultra medals and a half-marathon personal best of 2:04.

Lifestyle?

Is ‘overweight’ necessarily caused by a sedentary lifestyle? Spend a day in the life of Bakker, a live-in house mom at Rustenburg Girls’ High School in Rondebosch, and the answer is definitely ‘no’.

Bakker has always worked with youth, whether as a youth leader, au pair or swimming coach. She was 40 when Rustenburg’s hostel superintendent remembered her from a church youth group, and asked her to get involved in working with the girls at Rustenburg’s boarding-house hostel.

With 76 teenage residents the hostel is a hive of activity, from the moment the girls wake up, to the gentle chatter of a midnight feast. Bakker walks around the entire hostel, keeping an eye on the rooms and dorms and checking in on sick children.

Besides taking the girls out in the hostel bus for energetic activities like surfing, hiking, and ice-skating, she’s even taken a boarder and 15 of her friends out for a singsong birthday celebration. She often goes the extra mile, although she sees being available to the teens as part of her job. She once took a girl to the hospital in the middle of the night and stayed with her until morning.

“I love to laugh with the girls and connect on our fun trips out,” she says. “Or when we’re playing a game of 30 Seconds, or toasting marshmallows on sticks around a fire.”

Bakker started the hostel’s running club at the end of 2013, because she wanted to help the girls discover their own talents, and empower them with essential life skills. And running has filled these teens with the confidence that she never had growing up.

“Ms Bakker was always supportive, especially if there were some of us who weren’t fit, or natural runners,” recalls ex-Rustenburg Girls’ High student Robyn Patterson. “She isn’t a fast runner, and would stay at the back; but when we reached stop streets, she encouraged us to run back to fetch her. Our sessions were never cancelled, even if it was cold or if we didn’t feel like it.

“Running with Ms B didn’t just improve our fitness. Her passion for running and leading a healthy lifestyle, despite the obstacles, taught us that goals require perseverance.”

Diet?

Food isn’t the culprit either. Bakker loves food. Sometimes she struggles with her portions, and battles to resist sugar and make good food choices; but mostly she follows a balanced diet. For breakfast, she has eggs and a piece of low-GI bread, or yoghurt with nuts, a piece of fruit for a mid-morning snack, chicken or tuna with salad at lunchtime, and chicken or fish with vegetables for dinner.

“I enjoy healthy food, particularly avocados and vegetables,” she says. “I stay away from white bread and hot chips, which is quite difficult living in a hostel. On a cold winter’s day, I’ll walk into the dining room and there’ll be hot chips, steak and pies on the table. Maybe I’ll grab a few chips, but that’s all. Twice a week, I’ll treat myself to a quarter of a slice of cake, or two squares of chocolate.”

Genetics?

Bakker has become a runner in every sense, from racing to nutrition. But while no longer obese, she has remained overweight. According to Goedecke, not everyone can be slim by following a high-quality diet and exercising.

Genetics play an important role in weight. If everyone ran 10 kilometres a day and ate the same healthy diet, the outcome would still be a broad range of different body shapes.

“Some will always be more prone to being overweight than others, and will therefore have to work harder to maintain a healthy weight,” Goedecke explains.

Bakker isn’t saying ‘I’ve made it, and I know all the answers’. For her sense of self worth and where her life is today, she credits her Christian faith. In an ideal world, she’d love to lose another 10 or 15 kilograms, and be lighter so that she could run faster.

But at the same time, she has accepted that to call herself a runner, she doesn’t have to be the kind of ‘perfection’ you see on the cover of a magazine.

Inspired? Start your journey to running and weight loss, or try one of our training programmes.

READ MORE ON: weight loss