After The Fall: The Story of Zola Budd

Think you know the whole story of Zola Budd? Think again.

Think you know the story of Zola Budd? Think again. Even if you remember how the barefoot prodigy broke world records, became a symbol of South Africa’s oppression, and was blamed for Mary Decker’s Olympic nightmare, her story has more heartbreak, more hard-fought redemption, and considerably more weirdness than the legend.

Last autumn, at a pretty clearing Nestled 3,333 feet above sea level in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, 194 female collegiate distance runners gathered to run a 5,000-metre cross-country race.

Many were tall and slim, rangy and loose-limbed in the way of college-aged distance runners. They came from North Carolina State and Clemson and Davidson and Miami and other colleges and universities, and it’s a safe bet that no matter what burdens any of them quietly carried – anxiety about grades, boyfriend troubles, or less specific but no less real woes – none had ever faced the combination of worldwide shame and personal loss that had battered the middle-aged woman in their midst.

She was neither tall nor slim nor rangy. She was 42, brown as a walnut, slightly thick in the middle. When the race started, she jumped in front. The young runners knew this was an open race, that oddballs could run if they wanted. But what was the runner in front thinking? Maybe she wanted to feel the sensation of leading a race. Maybe she would quit after a few hundred metres, then limp back to her grandkids and tell them about the day she led some real runners. Maybe she used to lead races, back in her day.

Some of the coaches looked at each other. She had a nice stride – there was power to it, and precision. She wasn’t just a weekend jogger out for a laugh. The coaches could tell that, even if some of the young runners could not. She kept the lead even after 400 metres. More coaches watched her, and for at least one of them, and maybe more, who beheld her curly hair, and her speed, and the way she had that little hitch in her style – elbows slightly too high, a little too wide – there was something familiar.

Her coach had told her to take it easy, that she didn’t have to lead from the beginning. He had warned her against going out too fast. He had warned her that a gigantic hill sat in the middle of the course, and that if she went out too fast, the hill might swallow her. Now more coaches were looking at her, a curly haired, middle-aged woman, legs like pistons, elbows flying. What they saw didn’t make sense. She was decimating their college athletes. She ran the first 1.6km of the race in 5:18.

No slightly thick, middle-aged jogger could maintain that kind of pace. She was slowing down. And now the giant hill in the middle of the course was looming. And the young athletes were tracking the sun-cured, curly-haired rabbit down. They were clear-eyed, long-limbed, remorseless. They were on the big hill now, and they had caught up to her and they were going to pass her. Her coach couldn’t help it. She had ignored his advice. Still, he couldn’t help it. So Jeff Jacobs yelled. “Go, Zola!”

“Zola?” another coach asked, and stared at the runner. Other coaches stared, too. Zola? It was impossible.

Mention the name Zola Budd to the casual track fan and you’ll likely get one (or all) of three responses: Barefoot. South African. Tripped Mary Decker. Those were the boldest brush strokes of her narrative, and they continue to be. But the legend of Zola Budd is, like all legends, simple and moving and incomplete. It is made of half-truths, exaggerations, and outright lies. She did run barefoot – but so did everyone else where she grew up. She did refrain from speaking out against great and terrible injustice – but so did a lot of other people older and wiser. She did suffer stunning setbacks and tragic losses, but much of her misfortune was worse than people knew, the losses more complicated and painful than most imagined.

A lot of people thought she had disappeared and stopped running for good. But here she was.

“Go, Zola!” Jacobs yelled and another coach took up the cry, then another. Was it nostalgia, or a wish for their own faded youth, or a belated and overdue recognition of grit’s enduring majesty? Here she was, doing what she had always done, even when no one was watching. Through all the fragile triumphs and shifting tribulations of Zola Budd’s life – some well known, some known not at all – only one thing remained immutable: running. Once she ran to connect with someone she loved. Then she ran to be alone. Running brought her international fame and then worldwide scorn and then it brought her something few might suspect.

“Go, Zola, go!” The young runners closed again. Certainly they could hear the yells. What the hell was a Zola? It didn’t matter. They had time, and nature and physics, on their side. They had young legs. They had grit themselves. They would show this middle-aged mom what racing was all about. They reeled her in, and she pumped harder, faster and they reeled her in again. There was a long way to go.

Running had been fun for the curly-haired athlete once, a long time ago, and then it had saved her when she needed saving most, and then it had almost destroyed her before she was even an adult. Why was she running now? What was she running from? Or toward?

“Go, Zola!” the coaches yelled. “Go, Zola, go.”

Frank Budd and Hendrina Wilhelmina de Swardt, whom everyone called Tossie, had five children before Zola. Their third-born child, Frank Jr., died of a viral infection when he was just 11 months old. When Zola was born six years later, Tossie was in labour for three days and received six litres of blood.

“The nurses told me the kid’s a stayer,” Frank, always good for a quote, would tell reporters years later, before things got ugly.

When Zola was young, her father was busy working at the printing plant his father, an English immigrant, had founded – and Tossie was sickly. The oldest of the Budd children, Jenny, became the toddler’s de facto caretaker. Jenny was 11 when her baby sister was born and she read to her often. Their favourite was “Jock of the Bushveld.” It’s the true tale of a Staffordshire Bull Terrier, the runt of the litter who is saved from drowning by his owner and repays the favour by developing into a courageous and noble champion. When Zola started talking, according to family stories, Jenny was the first person she called “mom.”

Zola was skinny and short and terrible at swimming and team sports, but Jenny liked running, so when Zola got old enough, she ran, too. They ran over the hills surrounding Bloemfontein, the South African city of 500,000 where they lived. The city sits at 4,500 feet and when they ran in the morning, the air was chilly and clear. They ran barefoot, because all children in rural South Africa ran barefoot. They ran for fun. And they ran for something Zola would lose and not find again until decades later.

Then she got fast. And once the world discovered Zola and reporters started calling her things like “a prodigy among prodigies” and a “barefoot, waiflike child champion,” running was no longer about fun. Once the skinny, undersized adolescent became a champion, and then a symbol, and then a target of the world’s righteous wrath – at an age when other kids are entering college – running would be about everything but fun. Things were so much simpler when Zola was just a little girl, running barefoot through the hills with the big sister she idolised.

Later, there would be tales that Zola developed her speed racing ostriches, that her greedy father pushed her until she broke. Like many of the stories that swirled around Budd, they were half-truths. There were ostriches on the family property, more a large menagerie than farm, but she never raced them. And perhaps her father did push her – he saw how fast she was and got her a coach – but no one pushed her as much as she pushed herself.

It was a happy childhood. In addition to the ostriches, there were cows and ducks and geese. There were snow-white chickens her father bred and sold, and a water-pumping windmill. There was a family Doberman named Dobie. There were mud fights in the summer and in the winter, bonfires when Zola and her brothers and sisters would build fires and stuff firecrackers in glass bottles, then light them and watch them explode in the air. But Frank and Tossie didn’t get along, and the shadow of little Frank’s death seemed to always hover over the family. There were photographs of the missing baby all over the house and every year during holidays and on little Frank’s birthday, Tossie grew quieter, and sadder. It was a childhood filled with mysterious woe and delirious joy. It was a normal childhood.

FOREIGN INTRIGUE Onlookers watched Budd train on a hometown game reserve in 1983. / Photo by Mark Sherman / Athletics Images

Zola’s coach got her running more and Jenny became a nurse and wasn’t around as much. She worked the night shift and she would come home just as the family was having breakfast, and she would have a piece of cake or pie – Jenny always had a sweet tooth – and then she would go to sleep as Zola went off to school. When Zola needed to talk to someone, though, Jenny was always there.

Zola was fast, but not that fast. When she was 13, in a local 4K race, running as hard as she could, she came in second. By the time she crossed the finish line, the winner was in her track suit, warming down. Zola didn’t like losing. But she had the rest of her life. Besides, it’s not as if she was going to run for a living. There was school. There were her friends. And there was Jenny. All part of a normal childhood, which ended in 1980.

Jenny, then 25, had been in the hospital for a few weeks, being treated for melanoma. Zola was not allowed to visit. She was only 14, and Tossie knew how her youngest felt about Jenny. So Zola stayed home while doctors treated Jenny. Zola knew Jenny was sick, but she didn’t know how sick.

Cara Budd, then 18, came into Zola’s room at 4 a. m. on September 9. (Coincidently, it was Tossie’s birthday.) Cara woke her little sister and told her the news. Jenny was gone.

Zola didn’t cry or scream. She had always been quiet, had always kept her grief, and her joy, to herself. The only person she had really shared her feelings with was Jenny.

After Jenny died, no one in the family talked about it. A family that had never talked about its losses didn’t talk about this loss. Zola? Zola ran harder than she had run before. She would get up at 4:45 and run for 30 to 45 minutes. She attended school till 1:30, then went home and did her homework, then she would run some more from 5 till 7. Frank and Tossie and their children just tried to carry on. There were four kids now. Estelle, 23, the twins, Cara and Quintus, 18, and Zola. They had lost a baby and survived. And now they had lost Jenny. They would survive that, too. Zola? There was no one for Zola to talk to about Jenny’s death, or her life, or how she was feeling. She ran harder.

That winter, she entered the same local 4K she had lost the year before. This time she won.

She ran harder and still the pain of Jenny’s loss stayed with her.

The next year, she won the South African junior championships at 800 metres, and the year after that, the South African national championships at 1500 and 3,000 metres. She was still in high school and her normal childhood was just a blurry story, one that would be embellished and twisted and disfigured the more it receded into the past. A few years after Jenny’s death, she ran 5,000 metres in 15:01.83, faster than any woman had ever run it before and life would never be normal for Zola again. She didn’t know it, though. She didn’t know the terrible places running would take her.

When she set the mark in the 5,000 metres, she says, “That’s when I realised, ‘Hey, I’m not too bad.’”

She wasn’t the only one.

John Bryant was a runner, a writer, and the man in charge of the features department at London’s Daily Mail. So when he pored over some race results “lurking in the small print of Runner’s World” in 1983, his response was akin to that of a geologist eyeballing a ribbon of diamonds in a fetid swamp. Impossible, ridiculous, too good to be true, an invitation to a Fleet Street sportswriter’s doomed-to-be- dashed dreams. Absurd – but worth checking out.

“If the results were to be believed,” Bryant would write 25 years later, “there was a teenage girl, running without shoes, at altitude, up against domestic opposition, who was threatening to break world records.” (Budd’s 5,000-metre mark wasn’t ratified because it had been set in a race in South Africa, then banned from international competition due to its apartheid policies.)

What Bryant didn’t write: Budd was white. The racial angle, combined with the fact that Budd was South African, made the story irresistible. That the Olympics were coming up later that year and that South Africa was banned from participating, set in motion a chain of events that changed Budd forever.

Bryant dispatched a reporter to Bloemfontein. Other reporters were there, too. They found the shy schoolgirl, watched her glide over the hills, elbows a little high and a little wide, saw pictures of British middle-distance superstars Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett next to her pillow and above her bed, a huge poster of America’s track sweetheart, Mary Decker (whose 5,000-metre record Budd had bested by nearly seven seconds).

She was only 1.58 metres tall and weighed just 41 kilograms, but already she was larger than life. The reporters wrote about Budd’s parrot, who could swear in Sotho, a regional dialect. They wrote about Budd’s speed, about the impalas and springbok in the city’s game park who stared at the teen as she ran in the dawn’s chill. Reporters didn’t dig into Jenny’s death or Frank and Tossie’s rocky relationship. They didn’t examine the crucible of grief in which Budd’s speed had annealed.

At least one journalist, though, worried about the young runner. Kenny Moore, then with Sports Illustrated, described Budd’s failed 1984 attempt to break the world record in the 3,000 metres, at a race near Cape Town. After the setback, he wrote, “As photographers paced and growled outside, Zola sat hunched in a corner of the stadium offices, like a frightened fawn. If a true perfectionist is measured by how crushing even his or her perceived failure can be, Zola Budd is an esteemed member of the club. One wishes for her always to have loving, soothing people around.”

Bryant’s newspaper offered the Budd family £100,000 in exchange for exclusive rights to Budd’s life story. The paper also promised to fast-track the teenager so that she would receive a British passport. That would allow her to run in the Olympics. (Budd could qualify because of her grandfather’s British birth. It also helped that her father’s business wasn’t doing so well, and, as Bryant later wrote, that one of Frank Budd’s two great life ambitions was to retire with £1 million in the bank. The other was to have tea with the queen of England.)

There were demonstrations when she arrived in England. People booed her. People shouted insults. She was a white South African, a privileged white teenager from a racist nation, using a technicality to pursue nakedly personal ambition. Few knew about Jenny, how running had once been Zola’s way of spending time with her sister, then had become Zola’s way of mourning her. Few knew of her father’s failing business. She had never told anyone that. She had never been good at explaining herself. And she wasn’t any good at it now.

“She was such a shy and introverted person,” says Cornelia Burki, a South African-born distance runner who had moved to Switzerland in 1973 and represented that country in the 1980, 1984, and 1988 Olympics. She had befriended Budd, 13 years her junior, at the race in South Africa where Budd set the world record at 5,000 metres. She knew how Budd reacted to attention, how she shrank into herself. “All she wanted was to run, “ Burki says, “and to run fast.”

But the world wanted something else. At her first race in England, the Daily Mail held a press conference beforehand, and pumped in the sound track from Chariots of Fire. The BBC televised the 3,000-metre event, which Budd won in 9:02.06. That single effort was fast enough to qualify her for the Olympic Games. A columnist for the Mail called Budd the “hottest property in world athletics.” The Daily Mail’s chief competitor did not have access to the hot property. That newspaper ran a banner headline on its front page: “Zola, Go Home!”

“To the world,” a New York Times reporter wrote last year, “Budd was a remorseless symbol of South Africa’s segregationist policies. To the Daily Mail, she was a circulation windfall.”

And to the girl? “Until I got to London in 1984, I never knew Nelson Mandela existed,” she told a reporter in 2002. “I was brought up ignorant of what was going on. All I knew was the white side expressed in South African newspapers – that if we had no apartheid, our whole economy would collapse. Only much later did I realise I’d been lied to by the state.”

She wasn’t a racist, any more than any 18-year-old citizen of apartheid nation is a racist. She wasn’t an opportunist, any more than any fiercely competitive champion is an opportunist. But was she a champion?

She captured the English national championships at 1500 metres. In July, in London, she set a world record of 5:33.15 in the 2,000 metres. It was an odd distance, rarely run. But it inspired a British journalist to articulate something a lot of other people were feeling.

“The message will now be flashed around the world,” exclaimed a BBC reporter after the race. “Zola Budd is no myth.”

No myth, perhaps. But what a story! “The legs of an antelope,” one reporter wrote later, with the enthusiasm and penchant for empurpled prose Budd seemed to inspire among the ink-stained, “the face of an angel and the luck of a leper.”

She was a barefoot teenager, an international villain, the poor little swift girl. The best part? She would be competing in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics against her idol, a former phenom herself, another runner who drove writers to breathless, pulpy heights.

Pig-tailed and weighing 40 kilograms, Mary Teresa Decker, aka “Little Mary Decker,” burst onto the international track scene when she was just 14, when she won a U.S.-Soviet race in Minsk, in 1973. Over the next decade, she’d set world records at every distance between 800 metres and 10,000 metres. She was pretty. She was white. And she was American. But she had never run in the Olympics. An injury had kept her from the 1976 Games. The U. S. boycott prevented her from running in 1980.

A made-to-order arch-rivalry. Mop-topped schoolgirl vs. America’s sweetheart. One-time wunderkind’s last chance at Olympic gold, and the only thing standing in her way was a skinny kid who had once slept beneath her poster. Another irresistible tale, and like all the fictions surrounding Zola Budd, it left out a lot.

For one thing, Budd was wary about Romania’s Maricica Puica, the reigning world cross-country champion. For another, Budd had strained her hamstring training four days earlier, during a speed workout, and knew she wasn’t at full strength. Finally, there was the ever-quotable, ever-ambitious Frank.

Zola was making lots of money now – from the newspaper deal, from fees for showing up at races, from pending endorsement deals – and Frank was taking a huge chunk and wanted more. Zola told her father to knock it off, to let her be. Frank loved England, loved the high life. He was also harbouring a secret that would later provide more tabloid headlines. Tossie, who had been incapable of comforting her youngest daughter when Jenny died, was doing her best now – she cared not a bit how fast Zola ran, nor whether she ran at all – but she longed for the quiet of Bloemfontein. Frank and Tossie’s relationship, never placid, grew more turbulent. And two weeks before the Olympics, Zola told her dad he couldn’t come to Los Angeles to watch her run. She was sick of his money-grubbing, tired of his meddling, weary of the drama. So Frank stayed in England, stewing, and Zola and her mom flew to Los Angeles. And shortly after, Frank stopped talking to either his daughter or his wife.

The Olympic narrative was Decker vs. Budd. The reality was a lonely, miserable teenager who knew too much. “Emotionally,” Budd says, “I was upset, away from home, missed my family, by myself, it wasn’t the greatest time of my life, to be honest. I thought, Just get in this Olympics and get it over with.”

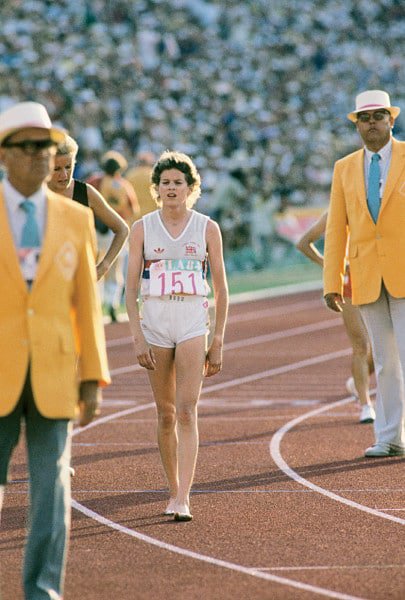

In the highly awaited 3,000-metre final, Decker set the pace, followed closely by Puica, Budd, and England’s Wendy Sly. When the pace slowed slightly about 1600 metres into the race, Budd picked it up, running wide of Decker, then, as she passed her, cut back toward the inside and the lead. Decker bumped Budd’s left foot with her right thigh, knocking her off balance. Budd kept running, and Decker stayed close, clipping Budd’s calf with her right shoe. There was a contact a third time and Decker fell, ripping the number right off Budd’s back. Budd kept running.

Boos rained down from the stands. Later, people would suggest Budd had pulled a dirty move, trying to cut off competitors, especially Decker. Others would say the maneuver showed the teenager’s relative inexperience in world events.

It wasn’t a dirty move. In fact, when a runner moves in front, it is incumbent on trailing racers to avoid contact. (Ironically, Budd says she made the move to get out of harm’s way. “If you’re running barefoot,” she says, “it’s best to be last or in front.”)

The L.A. Coliseum echoed with more boos.

“I saw what happened,” says Burki, who finished fifth in the race. “I saw Mary pushed Zola from the back. Zola overtook Mary and Mary didn’t want to give that position in front. Mary ran into Zola from the back…As she fell down, she pushed Zola.”

Budd pumped her elbows, kept running. She still didn’t think she’d win – she says that she suspected Puica would soon pass her. But the full impact of the situation didn’t hit her until she’d completed another lap and saw Decker stretched out on the ground, wailing. Puica and Sly passed Budd, but she passed them back. Then, she says, she started hearing the jeers and boos. The runners passed Budd again. Then another runner passed her. Then another. And another. Budd finished seventh, looking miserable. “The main concern was if I win a medal,” Budd says. “I’d have to stand on the winner’s podium and I didn’t want to do that.”

In the tunnel, right after the event ended, Budd saw Decker sitting down and approached her. She was so sorry the way things had turned out. She apologised to her idol.

“Get out of here!” Decker spat. “I won’t talk to you.”

Burki saw that, too. “Mary was sitting there crying. Zola was walking in front of me, apologising. Mary was screaming at her, I’ll never forget that. Zola being such a shy person, her shoulders dropped. It could have happened in any race, and it wasn’t Zola’s fault, but the blame was on her. For any young girl to cope with that, that was very difficult.”

Later, at a press conference, Decker blamed Budd.

Officials disqualified her from the race (and an hour later, after reviewing the videotape, rescinded the disqualification). She skipped the press conference, boarded the bus carrying British Olympic athletes. In one seat was a young woman, weeping.

Budd had always been polite. “Why are you crying?” she asked the woman.

“Because of what they did to you,” the young athlete told the runner.

A quarter century later, Budd still recalls the moment. “That was one of the nicest things anyone has ever done for me.”

Budd’s coach picked her up and took her to meet her mother. Budd had taken down America’s Sweetheart. She had sidestepped sanctions against her native country – that amounted to cheating, said some. So many rich, false narratives about the young girl, and the only one who cared nothing about any of them was the person who cared most about her.

“It didn’t matter to her that I didn’t win a medal,” Budd remembers. “She was just glad and happy that I was with her again, that we could be together.” They stayed in her coach’s suite at a local hotel. It was there that they received a telephone call from the manager of the British women’s Olympic track team. She was calling to pass on the news that there had been threats that Budd was going to be shot. Two police cars were on their way. When they showed up, the officers had submachine guns.

“They picked me up at the hotel and drove me and Mom to the airport, right onto the tarmac, and watched as we got onto the plane. It was like a movie.”

I have wanted to write you for a long time,” Decker wrote to Budd in December 1984. “…I simply want to apologise to you for hurting your feelings at the Olympics…It was a very hard moment for me emotionally and I reacted in an emotional manner. The next time we meet I would like to shake your hand and let everything that has happened be put behind us. Who knows? Sometimes even the fiercest competitors become friends.”

Publicly, though, Decker was not quite so soft. “I don’t feel that I have any reason to apologize,” Decker told a reporter in January 1985. “I was wronged, like anyone else in that situation.”

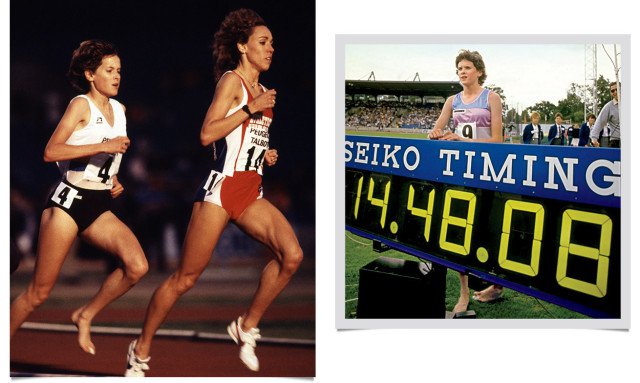

When she was a child, and endured her greatest loss, Budd ran harder. She did the same thing now, in the wake of Olympic infamy. Budd won world cross-county championships in 1985 and 1986, set world records in the 5,000 and indoor 3,000. But her parents divorced in 1986, and then she had absolutely no contact with her father. He had another life now. She ran harder. But what had once, a long time ago, provided Budd a refuge from grief now provided her detractors an opportunity to attack.

Well-meaning people asked her to speak out against apartheid. Movement leaders demanded she speak out. Why didn’t she renounce her country’s racist policies? She was naive, that was indisputable. She was also stubborn.

“My attitude is that, as a sportswoman, I should have the right to pursue my chosen discipline in peace,” she wrote in her autobiography, published in 1989. “…Seb Coe does not get asked to denounce Soviet expansionism; and Carl Lewis is not required to express his view on the Contra arms scandal. But I was not afforded that courtesy and it became a matter of principle for me not to give those who were intent on discrediting me the satisfaction of hearing me say what they most wanted to hear.”

But now, on her terms, she would speak her piece. She wrote in the same book: “The Bible says men are born equal before God. I can’t reconcile segregation along racial lines with the words of the Bible. As a Christian, I find apartheid intolerable.”

That was a nice sentiment, but for many, too little, too late. In April 1988, the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) told the British Amateur Athletic Board (BAAB) that it should ban Budd from competition because she had appeared at – but not competed in – a road race in South Africa.

She had suffered insults and accusations for years. Why does a runner, plagued for kilometres and years by a creaky knee, or a pebble in her shoe, or an aching tendon, finally quit? Is it a new pain, or just too much of the same?

A doctor examined her in London and declared her “a pitiful sight, prone to bouts of crying and deep depressions…[with] all the clinical signs of anxiety.” She decided to fly back to South Africa, to Bloemfontein. She told the press back home, “I have been made to feel like a criminal. I have been continuously hounded, and I can’t take it anymore.”

Back in Bloemfontein, away from the angry eyes of the world, she met a man, Michael Pieterse, the son of a wealthy businessman and co-owner of a local liquor store. They married on April 15, 1989. Zola invited her estranged father to the wedding (she had reached out to him once before, but he had maintained his silence). She asked her brother, Quintus, to give her away at the ceremony. When Frank heard that, he told his son that if he accompanied Zola, Quintus would be written out of his father’s will. Zola promptly disinvited her father to her wedding, which prompted him to tell a reporter, “I no longer have a daughter called Zola.” (Pieterse’s father walked Zola down the aisle.)

In his will, Frank Budd stated that neither Tossie nor Zola and her sisters should be allowed to attend his funeral, if he died before them.

Five months later, in September, Quintus discovered Frank Budd’s bloody body at his house. He had been shot twice, by his own shotgun, and his pick-up truck and checkbook had been stolen. The next day, a 24-year-old man was arrested. He claimed that Budd had made a sexual advance, and that it had triggered the killing. (The killer was later convicted of theft and murder, but given only 12 years due to “extenuating circumstances.”)

A murdered father who apparently had been leading a secret life. Worldwide enmity. She ran. In 1991, in her native country, she ran the second fastest time in the world over 3,000 metres. With repeal of apartheid and South Africa’s welcome back to the Olympics, Budd raced in the 3,000 metres at the 1992 Games in Barcelona. She didn’t qualify for the final. In 1993, she finished fourth at the World Cross-Country Championships.

And then, as far as the world was concerned, she disappeared. As far as the world was concerned, she stopped running.

All the teenagers were chasing her. She had grown up too fast, and now she was being chased by runners half her age.

The course wound over hills, at altitude. It must have seemed high to the girls who had been training at sea level. To a runner who remembered the chilly dawn of the African veld, it must have felt like home.

“Go Zola, go!”

Once reviled, once booed, the antiheroine of all sorts of compelling and not-quite-complete stories kept going. No one was booing now. People were cheering, yelling her name. She kept going and the young runners fell behind and she won the race in 17:58. Afterward, the coaches from the teams surrounded her. They wanted to meet the legend.

“They had heard about her,” Jacobs said. “But who had ever met the real Zola Budd?”

The legend comes to the door of her Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, house barefoot, of course, in shorts and a T-shirt that says “Does Not Play Well With Others” and a picture of Stewie, the cartoon baby from Family Guy. She turned 43 in May. She walks a little bit bowlegged. She has agreed to meet because she has always been agreeable, even when she didn’t understand what she was agreeing to. She says she’s working on that.

She is finishing her dissertation to obtain her master’s degree in counselling. She’s also working as an assistant coach for Coastal Carolina University’s women’s track team, which allows her to travel with the team and compete in open events. The men’s head track coach, Jeff Jacobs, coaches her. She says that people who have gone through pain can help others understand and endure pain. She says that long-distance runners are privy to a special relationship with pain and solitude and grace, and “I doubt that sprinters have that.”

She ran her first marathon in London in 2003, but dropped at 37 kilometres, depleted. She ran a marathon in Bloemfontein in 2008, and logged 3:10. Last year, she entered the New York City Marathon and ran 2:59:51. She’s planning on racing a half marathon by year’s end, and a marathon next year. In the meantime, she wants to compete on the master’s circuit, “in as many local cross-country races and local 10K and 5K races as possible.” But that’s not the focus of her life. She had a baby girl in 1995 and twins, a boy and girl, in 1998 and she’s just a mother, she says now, just a wife. Yes, she knows it’s 25 years since she was blamed for destroying the dreams of America’s Sweetheart. No, it wasn’t her fault. Yes, she knows people are still curious about it. She is pleasant without being effusive, charming without being gushy.

Over three days in the early summer, she says that her accomplishments mean little, that her disappointments even less. She smiles. It’s a shy smile, almost an apologetic one. She doesn’t want to push her kids. She knows what it’s like to be pushed. She treasures the moments of her childhood when no one was pushing her, before she had discovered her gifts, before the world had discovered them and adored them and twisted them to its own purposes.

No, she says, she never quit running, just competing. She can’t imagine not running. The time she loved it best was before anyone – even she – knew how fast she was.

“I never strived to be the best in the world,” she says, softly, still smiling, remembering those happy days. “I just ran every day, I just ran.”

Her mother died four years ago and that was hard, and sad, but it was good, too, because all of Tossie’s children and grandchildren got to see her, got to say goodbye, to show her that she was beloved. Budd got to tell her mom how much she had always loved her, how much her support had meant, how when the world cared so much about how fast Zola ran and what country’s colors she wore and who she was competing against – about all the stories… it meant so much to have a mother who didn’t care at all, who ignored the stories, who just cared about who Zola was.

It was so unlike Frank’s death in 1989. Tossie and Zola had to comply with his will, so they couldn’t attend the funeral. Plus, there were the ugly stories in the papers. That was hard, too, and sad, and there was nothing good about it.

Fatherless, motherless, Budd has run through it all, elbows a little too high, a little too wide, and most of the world didn’t know, or care, and that made the running something better, something closer to what she had when she was young. Running helped her deal with her father’s death, as it had helped her deal with all the people calling her names and telling her she was things she was not. It helped when she discovered that her husband was having an affair four years ago. The story of Zola Budd was resurrected. New banner headlines, at least in South Africa. New sordid details – the other woman had been a socialite and beauty pageant contestant, nicknamed Pinkie. Michael had bought a house for her. She had called and threatened Zola. Zola says that Pinkie poisoned and killed one of her dogs.

She filed for divorce, and she told a reporter, when Michael denied that he had done anything wrong, “Why do all husbands deny it? I have no idea. But I have more than enough evidence that he is having an affair. More than enough.”

But she had been through worse, and when Michael got rid of Pinkie, Zola and her husband reconciled.

Not that she has forgotten. “Marriage is like cycling,” she says. (She has recently taken up mountain biking.) “There are only two types of cyclists, those who have fallen or those who are going to fall. Same with marriage, those who have had problems and those who are going to have problems.”

For someone whose mere name serves as shorthand for international drama, she could not seem more placid, more zen. “Running and other stuff passes away,” she says. “It’s old news. The legacy you leave for your kids, that lasts.”

She still holds British and South African records, at junior and senior levels. Her name is in the lyrics of a song once popular in her homeland. The reliable, long-distance jitneys in her hometown are called “Zola Budds” or just “Zolas.”

She doesn’t display any of her old medals. “They’re in a box somewhere in South Africa, I think.”

She says the happiest moments of her life occurred when her children were born. Where do her running victories rank in her spectrum of life’s happy moments? She barks a heavy laugh, as if that’s the most ridiculous question she has ever entertained, in a lifetime of entertaining ridiculous questions. “They don’t.”

She wants her children to grow up doing whatever they want to do. Anything at all, as long as it makes them happy. “Well, artists are never happy, are they? But fulfilled, I want them to be fulfilled.”

How does she think she’ll be remembered? She laughs again, but this time it’s an easy, light sound. “I have no idea. I never thought about that.”

She doesn’t mention her victory in the cross-country race. She doesn’t talk a lot about running. Yes, she thinks she was treated unfairly, but it was a strange time and her country was doing terrible things. No, she’s not a racist, and no one who knows her would ever think she was. No, she never became friends with Mary Decker, but they did make peace.

“Both of us have moved on and running isn’t so important in our lives,” she says. “We’re both a bit more wise.”

Which isn’t to say that running isn’t important at all to the champion. She might be placid, she might be serene, but she did hire a college coach to train her. She does compete against women half her age. The family received a two-year visa to live in the United States last year. Zola wanted to expose the kids to another country’s educational system. But she also wanted to try the master’s running circuit here. They chose Myrtle Beach because they wanted to be on the East Coast, which makes it easier to fly to their homeland, and because Michael loves golf, and there are more public golf courses in the Myrtle Beach area than almost anywhere else in the world. Zola does not play golf. “It’s dangerous if I play golf,” she says. “It’s better for everyone if I don’t play.”

She doesn’t watch sports on television. She does not watch the Olympics. She has watched her Olympic duel with Mary Decker only once, the day after it happened.

She wants to give her children what she once had as a child, before the world discovered her, before there was a story. She says she understands adolescents who cut themselves, “because physical pain can be better pain.” She remembers a time before she was aware of any emotional pain, when she was just “that young kid who plays barefoot on the farm.”

She talks about that kid a lot, about life on the farm, about the time when no one knew about her speed, when no one cared. She is asked about Jenny.

She grows quiet for a moment. She remembers that her sister’s favourite colour was green. She remembers that Jenny had her own dog, a pinscher named Tossie (after her mother) who followed her everywhere, and she remembers Jenny’s sweet tooth, and the way she would eat her pastry while the rest of the family sat down to breakfast, before she went upstairs, to sleep.

She remembers Jenny reading to her, and running beside her. She remembers the story of the little runt, Jock of the Bushveld, and how he grew up to be a brave, beloved champion. She remembers how when Jenny died, Zola attacked the hills and trails with a vengeance she never knew she possessed.

“Her death made everything in my life, even eating and drinking, seem of secondary importance…” Budd wrote in her autobiography. “Running was the easiest way to escape from the harsh reality of losing my sister because when I ran I didn’t have to think about life or death…There is no doubt that the loss of Jenny had a major effect on my running career. By escaping from her death I ran into world class…”

“[The family] did not talk about her death a lot afterward,” she wrote in a recent e-mail. “I started training a lot and that was it.”

Jenny has been gone for 30 years, but at the moment it’s as if she’s in the next room, in front of one of her morning pastries, or in her bedroom, pulling her curtains closed, getting ready to sleep. Budd talks about her sister quietly, and matter-of-factly, and then she quietly and matter-of-factly weeps.

“If Jenny hadn’t died,” she says, “I probably would have become a nurse.”

She talks about her father, too, and recounts the visit she made to his gravesite, where she made peace with him. She knows he suffered, too. She doesn’t believe her father made any advances against his killer.

Asked about her father in 2002, she told a reporter, “Back then South African society didn’t accept homosexuals. It took a terrible toll on him.” Today she says, “If he had been around now, he could have been more open about who he was.”

The intimate details that the world knows about Frank Budd are largely due to Zola’s fame. She knows that. She knows that his actions are part of the Zola Budd story. What she also knows – what the world doesn’t know – is he was a good dad, before all the money and fame and fighting. So much of what the world knows about Zola Budd is the simple story, the one with cartoon villains and epic struggles and bright, bold lines of right and wrong. But things were always more complicated than that. Frank Budd was greedy, and pushy, and that fit into a simple story, but he was other things, too. The world doesn’t know that Frank Budd watched a cow chase his little 10-year-old girl and the family dog, Dobie, and that he remarked on how fast she was, before anyone else had, and that the two of them laughed and laughed at how afraid of the cow she had been. The world doesn’t know that he constructed a little duck pond for his youngest child, and that she would tell him stories about how she took care of the ducks, that she fed them just like he told her to, that father and daughter loved each other and were happy, once upon a time before the world discovered her gifts, before the gifts became so heavy. She sheds a tear for her dad, too.

Running was so much fun when she was just a child, then it became a release, and finally, a means to an end she never wanted — money and political symbolism and international fame. It became so important. It became part of a larger narrative. And it wasn’t her narrative.

And now, even though she still is intensely competitive, even though she sometimes runs too hard for her own good and is preparing for a return to competition that may bring with it a lot of scrutiny that she never welcomed nor enjoyed, it’s okay, because she’s got her balance about her now. She knows what’s important. She knows what’s hers.

She’ll do her best in the upcoming marathons. She’ll do well in the master’s circuit, too. That’s the plan. Truth be told, she plans to kick some serious American ass, not that she would ever say that. She might be shy, and sensitive, and misunderstood and have the face of an angel and all that. But she is still a champion.

But that’s not why she’s running. Not to win. That was never the main reason she ran. That was never the real story.

Most people don’t think too much about why they run. They never have to, because running simply feels good and helps them. Zola Budd, though, has had to think about why she runs.

She runs not for medals or glory or to set anyone straight, either. Not to make anyone understand her. That never worked.

She runs for the thing that running once bestowed upon her, a long time ago, and that running almost snatched away. She is running to get it back.

“I run to be at peace,” she says.

Story Update · August 4, 2016

Zola Budd – now Zola Pieterse – reunited with Mary Decker Slaney in March for the first time in decades at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for the making of the documentary The Fall; the film premiered in the U.K. on July 27, although for now there is no word on when it might be released in other countries. “We had time to spend together and an opportunity to talk about things other than running and get to know each other,” Pieterse says. “One of the reasons both of us decided to do this is that it hopefully will give us closure.”

Last year, Pieterse became a full-time assistant track-and-field coach at Coastal Carolina University after volunteering with the team since 2008. She balances coaching with working on her masters in sports management (she also has a graduate degree in counselling) and raising her three kids: 20-year-old Lisa, and twin 18-year-olds Azelle and Michael. Pieterse is still a competitive runner at age 50, averaging 80-kilometre weeks. She finished seventh at South Africa’s Comrades Marathon in 2014 and ran her most recent marathon, the 2015 Columbia Marathon, in 3:05:26. She dropped out of this year’s Boston Marathon midrace – “Some days, you just don’t have it,” she says – but plans to run another marathon next spring. “Of all the athletes I’ve profiled, she seemed more at peace than anyone despite having gone through more bad stuff than most,” writer Steve Friedman says. “Her athletic accomplishments were so far from the most important things in her life.” – Nick Weldon

READ MORE ON: inspiring people olympics running