What The World Champs 10Ks Can Teach Us About Pacing

Here’s a detailed look at how the best runners in the world go about their business. – By Alex Hutchinson

Last week, I made some predictions about how the 10,000-metre races at the world championships in London would play out. Based on the patterns in past championships, I predicted we’d see a “time-to-exhaustion” race, where everyone simply stays with the leaders as long as possible instead of trying to run their own best sustainable pace. As crazy as it sounds, I expected that this would be the only way to be in contention for a medal.

So how did the races play out?

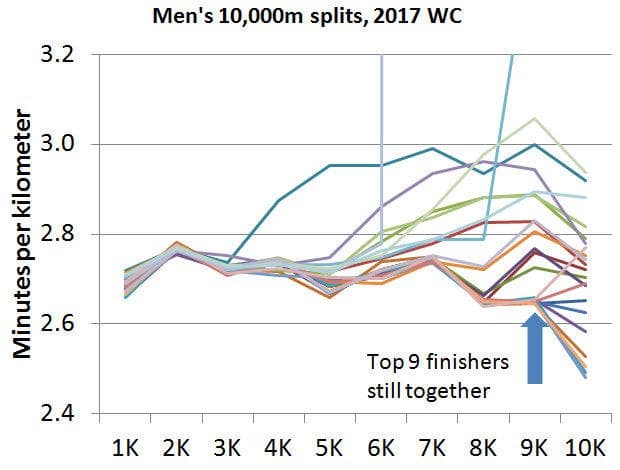

In the men’s race on Friday, an international coalition of the willing made the pace hot from the start, led by Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei and Kenya’s Geoffrey Kamworor, in an attempt to blunt the sting of Mo Farah’s famous finishing sprint. With every passing kilometre, another runner or two was shaken off the back of the back and left to limp home.

After 9K, there were still nine runners in a tight pack that had run every step of the way together. In the plot below, you can see the dramatic separation that occurred in the final kilometre. Some of the leading nine slowed dramatically, others accelerated – led by Farah, who won yet another global title.

But there’s a crucial point: No one caught any of the leading nine (though it was close). Once a runner dropped off the lead pack, he was never able to regain contact.

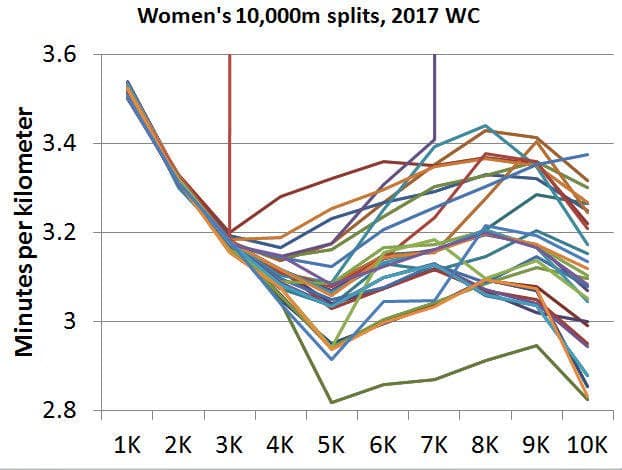

The women’s race was very different, thanks to the presence of a runner, the Ethiopian Almaz Ayana, who was dramatically better than everyone else in the field. Almaz ran a staggering world record in the Olympic final last year. This year, she was content to run at a modest pace for the first few kilometres before breaking the race open shortly before 5K.

Here’s what the splits looked like:

Once again, everyone started together. But Ayana’s acceleration before the halfway mark was so dramatic that there was no slow, one-by-one winnowing of the field, as there was in the men’s race. Instead, there was mayhem: By the time they hit halfway, this race was every woman for herself.

A small band of six women, led by the Kenyan-turned-Turkish runner Yasemin Can, did initially try to follow Ayana. Their fate is interesting.

Can’s line in the graph above is the second-fastest line at 5K, since she was trying to follow Ayana. She was still in the chase pack at 7K, but then drifted back and was caught by some of the other runners, winding up 11th.

Similarly, a few of the other would-be-chasers were caught, including Ethiopian-turned-Bahraini Shitaye Ashete and Kenyan Irene Cheptai. In my pre-race post, I suggested that to win a championship medal, you might have to be willing to run “irrationally” – but when you’re up against a runner of Ayana’s norm-defying caliber, there’s clearly a limit to how much irrationality you can survive.

From the second chase pack, the Netherlands’ Susan Krumins and American Emily Infeld closed best, finishing 5th and 6th. Their final kilometres were among the fastest in the race, allowing them to pass Cheptai, who was 12 seconds ahead of them at the 9K mark.

Still, the top three finishers behind Ayana all came from the initial chase pack that tried to follow her. No one was able to get on the podium by sitting back and keeping their tinder dry.

So, looking ahead to the 5,000-metre races this weekend, what lessons can we draw from these pacing patterns?

For the men, it should now be clear that Farah’s unprecedented championship dominance isn’t just the result of poor tactics by his competitors. He has shown the ability to win off fast paces as well as slow paces; the most that can be said is that he’s now very tired, so in a race that will likely come down to a matter of inches, his fresher competitors should have a chance. And anyone who wants to medal can’t afford to let any move go uncovered.

For the women, the picture is different. It’s highly tempting to suggest that everyone should simply pretend Ayana doesn’t exist, to avoid destroying their own races with an ill-advised attempt to follow her.

In reality, that doesn’t seem to be how the best runners in the world are wired. Hellen Obiri has run a Kenyan record of 14:18 this year, just six seconds behind Ayana’s best. It’s hard to picture her conceding the race without a fight – and indeed, I hope she doesn’t.

The big question, from a pacing and tactical perspective, is where the third medalist will come from. Will it be someone who runs for gold and sticks with the leaders as long as possible, or will it be someone who paces themselves to cagily run for bronze? My bet is the former, but I’m looking forward to seeing how it plays out.

READ MORE ON: IAAF World Championships iaaf world champs