When Is It Okay to Give Running Advice?

Know when to offer an opinion - and when to keep it to yourself.

Know when to offer an opinion – and when to keep it to yourself. – By Mark Remy

“You’re doing it wrong.” That, in my humble opinion, is one of the most underrated movie lines of all time – so underrated that most people don’t recognise it as a movie line at all.

The movie in question is Mr. Mom, the 1983 comedy starring Michael Keaton as Jack Butler, an auto engineer who loses his job and becomes a stay-at-home dad while his wife (Teri Garr) rejoins the workforce. (I know. Back then, this was a pretty wacky premise.) The scene in question involves Jack dropping his kids off at school for the first time.

As he pulls up to the building, in a pouring rain, Jack wonders why the other drivers are honking. “Because you’re doing it wrong,” says his son Alex.

Jack scoffs. “I know how to do this,” he mutters. At which point Annette, a smiling woman in a rain slicker, waves him down. He stops and lowers his window, and this happens: Annette: “Hello, Jack? I’m Annette.” Jack: “Hi.” Annette: “You’re doing it wrong.”

You have to see the scene to truly appreciate it – the timing and delivery, the body language, the angry woman who drives by and screams at Jack, “South to drop off, moron!” – but, in essence, there it is, brilliant in its bluntness. You’re doing it wrong.

In a world full of grey areas, of questionable assertions and (pardon my language) outright bull-pucky, how reassuring is it to find a bit of black and white? How bracing to be in a position to know someone is “doing it wrong” – and to tell them so?

RELATED: The 5 Worst Things to Do After Your Run

We runners pride ourselves on being strong and self-disciplined, and rightfully so. Finishing a marathon, gutting out a 5K PB, getting in a long run when it’s freezing cold or brutally hot. All demand great strength and tremendous self-discipline. None of them, however, compares to the strength and self-discipline required for a runner to restrain himself when someone is “doing it wrong.”

My own strength was tested recently when I heard a woman warning her young daughter, “Don’t drink too much water – it’ll give you cramps.” This was during a fundraiser at my daughter’s school. The kids were running around the small campus, earning money for each lap. I was a volunteer stationed near the water bottles, which is how I came to witness Mom cutting short her daughter’s sip.

The advice was bull-pucky. I knew that. I could have said so. But I didn’t.

Months earlier I’d been in a similar spot at a youth soccer practice. It involved a father critiquing his son’s running form as he raced up and down the sidelines. The kid was clearly enjoying himself, and his form looked just fine to me. Dad disagreed. “Your steps are too short!” he hollered. “Stretch out your legs and take long strides!”

This advice was 180 degrees wrong, about as wrong as wrong can be. Again, I almost spoke up. Again, I didn’t.

Why not? Mostly, I think, because both situations involved parents and their children. I know firsthand that telling a mother or father that they’re “doing parenthood wrong,” no matter how tactfully you say so, rarely ends well. Even in trivial matters.

But also because I’m tired. Tired of processing so many opinions on so many subjects from so many sources. Tired of this need that we all have to “weigh in” every chance we get – to second-guess and play armchair expert. Especially in trivial matters.

I fear it won’t be long before race volunteers start handing out advice with the goodies at the finish line:

Volunteer #1: “Congratulations!” (Loops medal around runner’s neck.)

Volunteer #2: “Water?” (Extends a bottle in each hand.)

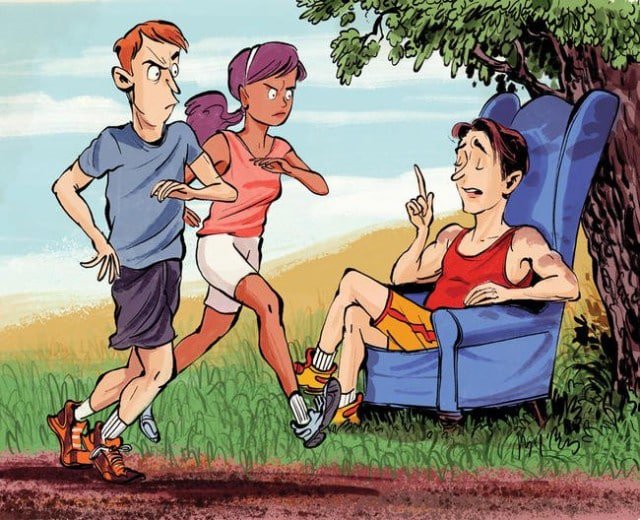

Volunteer #3: “You started too fast.” (Sits in actual armchair.)

I blame the internet for this, by the way. (I blame the internet for most things.) Busybodies and self-styled experts have always been around, of course, but the internet has enabled and amplified them in a huge way. And it doesn’t discriminate – awful advice has exactly the same reach as good advice, and superficially looks just as legit.

It’s also conditioned many of us to feel entitled to barge into conversations, sometimes those of total strangers, uninvited. Often it’s to offer advice or issue a “correction” where none is wanted or warranted – assuming we actually know what we’re talking about, which often, frankly, we don’t.

The good news – yes, there’s good news! – is that there are ways to rein this in. At least as far as our own behavior is concerned. I’m still very much a work in progress, but here’s what seems to work for me:

- Whenever I’m tempted to offer unsolicited advice, I ask myself, What happens if I don’t speak up? What’s at stake here? Usually the answer is “Not much.” If silence could result in pain or injury, then yes, I’ll say something. Otherwise, I keep my thoughts to myself.

- I try to embrace self-doubt, wondering whether my own information may be outdated or just plain wrong. Remember: Much like no one thinks he’s a bad driver, no one thinks he gives bad advice. We all have our blind spots.

- Dogma is dangerous. So when I do give advice – which almost always is after someone has asked for it – I bookend it with disclaimers and disclosures. Phrases like “In my own limited experience” or “Depends on who you ask” or “You’ll want to experiment and see what works for you” go a long way toward setting the proper tone.

In the end, I think, we’re best served when we turn our focus inward, becoming experts on ourselves – on what works for us – and letting others do likewise. Beyond that? Often the best advice is not to offer any.

Not that you asked.

Mark Remy is a Runner’s World writer at large and the mastermind of dumbrunner.com.