Survival Of The Fittest: Running Saved My Life!

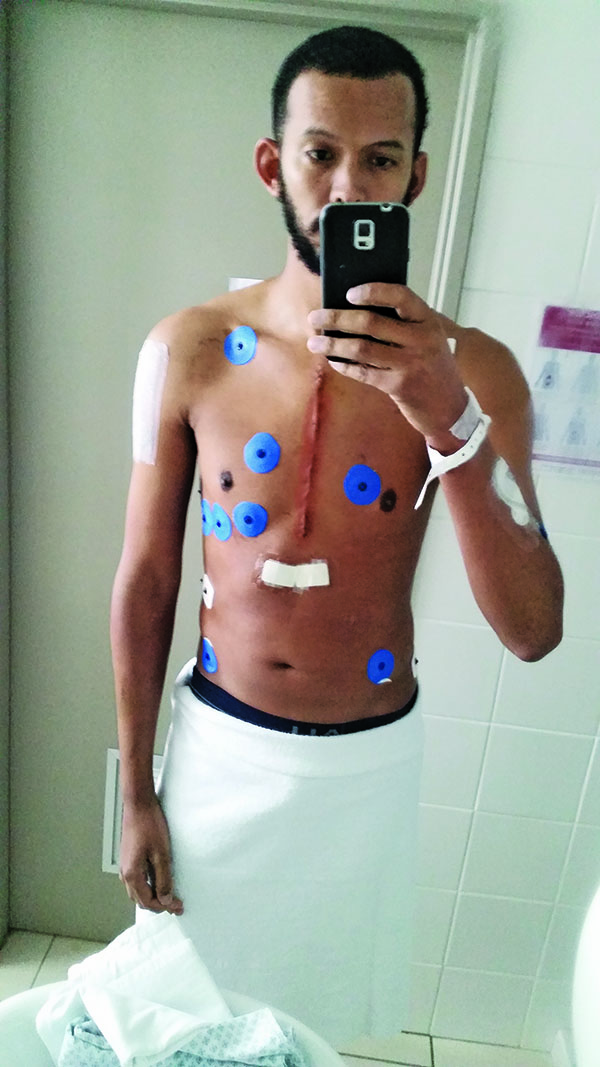

For Cape Town runner Lloyd Jacobs, hearing that he would have to undergo open-heart surgery was shocking. – By Lisa Abdellah

Besides the fact that there was no history of heart problems in his family, he was a young man in his early 30s, who ate healthily. A competitive trail runner, he had finished in the top 10 at the Cape Winter Trail Series. He had also achieved five Two Oceans Half medals.

It happened quickly. Up until two days before the diagnosis was made, he hadn’t experienced any of the symptoms associated with a cardiac incident. He had competed in the Trail Series on Sunday, and trained as usual on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday.

But on Thursday night, Jacobs noticed something was wrong.

“My resting heart rate rose to 150bpm. It was just going and going and going,” Jacobs remembers. “By Saturday, I had started coughing up blood.”

Concerned for his health, Jacobs went to Vincent Pallotti Hospital. Cardiologist Dr Jens Hitzeroth performed an ultrasound of his heart. His investigation revealed Jacobs’ mitral valve (which controls the flow of blood) was flapping about, leaking blood.

“Jacobs needed open-heart surgery, to replace the diseased mitral valve with an artificial one,” explains Hitzeroth.

“This major operation involves cutting the chest open, in particular the sternum (the breast bone in the middle of the chest).”

No going home

“My first thought was, Am I going to die?” Jacobs recalls. “My friends, colleagues and training partners couldn’t believe it either. They didn’t think someone with my sort of healthy lifestyle could be struck down with an ailment like this.

“Next question: When can I run again? The doctors told me I would recover, but they couldn’t give me a time frame.

“And finally: I drove here. What do I do with my car? It’s parked outside!”

Before the operation, Jacobs spent two agonising weeks in medical ICU while doctors looked for what had caused the problem. Kidney biopsies were taken. Tests for rheumatoid fever carried out. A piece of the valve was cultured, to see if anything would grow off it – nothing did. They never found the cause.

“Jacobs’ shortness of breath suggested a bacterial infection of the heart valves,” says Hitzeroth. “We had to rule out infection first, and then ensure he was well enough to survive open-heart surgery.”

Luckily, Jacobs was a runner.

“The fitter and healthier you are prior to any operation – especially open-heart surgery – the better your body will cope with the insult.

“In addition, the fact that Jacobs had achieved a healthy weight through running not only made the technical aspects of the surgery easier; it helped him to heal more rapidly, with fewer complications.”

A long recovery

The first three weeks of Jacobs’ recovery were spent in surgical ICU. They were traumatic. He was surrounded by terminally ill patients, four of whom passed away while he was there.

“I was really strung out and I couldn’t sleep, just sitting there like that,” he remembers.

Before Jacobs was discharged, he was transferred to a general ward for five days, where he was taken in hand by a physiotherapist.

But the support he received, Jacobs says, was amazing. He spent the next two months at home, where his mother Hazel looked after him. His workplace gave him 80 days sick leave, and got someone to cover for him.

Because his sternum had been cut right through, Jacobs couldn’t walk, sneeze, or laugh. Sometimes breathing was painful. If he wanted to sit on the couch, he had to lie completely flat.

Weak, slow and helpless, Jacobs had to depend on others to help him with tasks he’d found easy before. During the first week, he wasn’t able to shower without assistance. It took two people to help prop him up into a sitting position.

“Going from being able-bodied and competent, to a total drain on everyone around me… I felt like my legs had been cut off.”

But running had armed him with the positive attitude and mental toughness he needed for a speedy recovery. Jacobs’ goal of reaching 10 Two Oceans Half Marathons made him all the more determined to get back on his feet.

Small steps

After two months, he started walking – 100 metres at a time. A further two weeks, and he made it as far as the railway bridge 800 metres from his home.

When he was comfortable with a brisk three-kilometre walk, Jacobs asked a friend to drive him to Rondebosch Common.

Managing a three-kilometre run around the park was an emotional experience; afterwards, he sat in the car and cried.

“People wanted to help by tagging along. But running was something I needed to do on my own,” he says.

“I had to learn to feel my new heart valve, and accept the fact that I can’t run as fast as the guys who are chasing sub-two-hour times at the Two Oceans Half anymore.”

Life, but different

“Jacobs’ heart muscle wasn’t damaged by the diseased valve, so from a physical point of view, he can do any exercise he wants to,” says Hitzeroth. “Running is an excellent way for him to stay fit.”

Unfortunately, Jacobs’ artificial valve is made of metal, which causes blood to clot. To prevent that from happening internally, he must take an anticoagulant to thin the blood. But this means that if he suffers a fall or some other external injury, the wound won’t stop bleeding.

“When it comes to physical activity, I’m more careful now. I pace myself, and I’m aware of the possibility of getting hit or knocked on the chest,” he says.

“Obstacle races are out of the question. Running fast isn’t advisable either, because the impact of slowing down could jar my sternum.”

Recovering from surgery has been tough for Jacobs, but in many ways it has put things into perspective. Life is short; and had it not been for the positive role that running played in both his surgery and his recovery, his life might now be very different.

The experience has made Jacobs less self-centred, and more empathetic. These days, instead of postponing, he follows up on coffee dates with friends.

In the end, he finished the Two Oceans Half in close to three hours – which was a lot slower than he was used to. “But running that Two Oceans, to me, wasn’t about pride or ego anymore – it was a flat-out, tired-but-elated celebration of the fact that my body could run.”

Quite an achievement, considering Jacobs had been on a cardiologist’s operating table just seven months earlier. He realised on the finish line that it’s impossible to judge a book by its cover: the spectators (and his fellow participants), seeing this healthy, confident runner, couldn’t possibly know what he’d been through.

Running Recovery

Major surgery is physically and emotionally traumatic, but cardiologist Dr Jens Hitzeroth and oncologist Dr Mohamedtaki Tejani agree that runners can recover faster than non-runners…

- The fitter and healthier you are, the better your body will cope.

- A healthy weight means your body will heal more quickly, with fewer complications.

- You’ll approach your recovery with the same positive attitude and mental toughness you apply to running.

- Your desire to return to running will make you all the more determined to get back on your feet.

- Running is therapeutic. It will help you combat depression, and win back control of your life.

READ MORE ON: two-oceans