Above & Beyond Mount Everest

How trail-running legend Kilian Jornet’s record-breaking ‘run’ up the world’s highest peak has redefined the boundaries of our sport – and the very limits of human performance.

How trail-running legend Kilian Jornet’s record-breaking ‘run’ up the world’s highest peak has redefined the boundaries of our sport – and the very limits of human performance. – By Duncan Craig

At midnight on May 21, Kilian Jornet stood on top of the world.

He carried neither oxygen cylinders nor ropes, and no guides or Sherpas were at his side. The 29-year-old was alone, light and nimble – the torch beams of expensively assembled expeditions on the mountain far below punctuated the blackness. With his lightweight kit, a few energy gels and just a single litre of water, he looked more runner than mountaineer. Which, of course, is precisely what he is: the greatest mountain runner in history, in fact.

Seemingly not constrained by the same laws of physics as the rest of us, the Catalan mountain goat had just set a record for the fastest known time (FKT) ascending the planet’s most fabled peak: a scarcely believable 26 hours from base camp on the Tibetan side of Everest to the 8 848m summit.

Wearing custom-built shoes engineered by his sponsor Salomon, he’d run the first stretch in the style of one of the mountain trail-running races he’s dominated for nearly a decade, before pulling on crampons and advancing into the more technical terrain. Passing seasoned mountaineers taking up to four days to toil their way up into the ‘death zone’, he’d continued in a single push to the top. Some had scoffed at his aim to ‘run up’ Everest. But, by any relative measure, this was exactly what he had achieved.

“From the top, I could make out the neighbouring mountains, Cho La and Lhotse, the plateaus. It was truly beautiful,” says Jornet, typically more concerned with the value of the experience than the scale of his achievement. “Everybody can climb how they feel they want to – there’s no good or bad way. But for me, I wanted to see if it was possible to do it in one go, with no oxygen, no ropes, faster. My way: it felt good to be alone up there. To just enjoy the moment and not have to think about other people.”

A Himalayas novice Jornet may have been. But the Alps-based ultra runner knew more than enough about mountains to understand that the summit, as the saying goes, is only halfway. Despite the success of his FKT, the ascent had been far from straightforward – his 1.7m, 58kg frame was wracked by agonising cramps and vomiting exacerbated by extreme exertion in an environment entirely hostile to even the most physiologically gifted of humans. So, at that point, he’d abandoned his plan to descend all the way back down to Base Camp for a neatly bookended time. Instead, he holed up at Advanced Base Camp (ABC), at 6 500m, as the wind picked up. His instincts, as usual, were good; four people died on Everest’s slopes that weekend.

Mountain-running legend Marino Giacometti, pioneer of the high-altitude- trail Skyrunning movement that Jornet has done so much to popularise, followed his protégé’s exploits with both awe and apprehension from his native Italy. “This is a great achievement of both endurance and survival,” says Giacometti. “In trail-running terms, this is one of the great performances. No ropes, no oxygen. No one in the world could have done this except Kilian.”

The veteran explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes, a man not given to issuing breathless praise, particularly not to those who might be seen to be encroaching on his turf, goes even further in assessing Jornet’s talent and achievement: “Normal people – and in that I count myself – we have to accept that there are those who can do things which I would say for humans are not possible.”

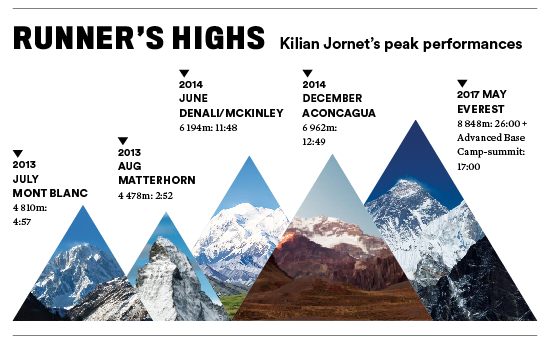

For Jornet, achieving the impossible in the Himalayas was merely the closing chapter in a five-year odyssey to set FKTs on the world’s most emblematic peaks. The Summits of My Life project began in 2012 with a sub-nine-hour ski-mountaineering traverse of Mont Blanc (4 801m), in the French Alps. Jornet followed this with a straight up-and-down of the Alpine giant from the centre of the mountain sports Mecca, Chamonix. Most mountaineers take two days to scale Mont Blanc, encumbered by heavy kit and complex logistics. Jornet did it in four hours and 57 minutes, wearing a T-shirt, shorts and trail-running shoes, breaking a record that had stood for 23 years in the process and commenting with characteristic understatement that “it was a nice experience”.

The 4 478m Matterhorn came in August the following year. Setting off from the elegant white church in the centre of Breuil-Cervinia, and following the classic Lion’s Crest route, Jornet raced up to the woven metal cross that teeters on the summit and back down in the time it takes most of us to log on in the morning, check our emails, have a coffee and consider doing some work: two hours and 52 minutes. The 18-year-old record he broke in the process had belonged to the great Italian mountain runner Bruno Brunod.

To view the jaw-dropping drone-captured video of Jornet’s performance that day (and if you haven’t, you can check it out at staging.runnersworld.co.za/kilian) is to watch one of the most accomplished athletes of all time operating at the peak of his powers. With mid-afternoon sunshine illuminating the snow-lined strata of the Matterhorn, the whippet-thin Catalan races up and down serrated, near-vertical rock faces at a pace that leaves your head spinning. During the 56 minutes it took him to get from the summit back down to his starting point, he descended at the remarkable rate of 2 645m per hour.

Brunod accompanied him along the final section of the route. “This is the moment that will remain engraved in my memory,” says a magnanimous Jornet. “If I am what I am today, I owe it to people like him, who have inspired me ever since I was a young boy.”

In 2014, Summits of My Life really gathered pace. Ascent-descent records fell to Jornet on Alaska’s 6 194m Denali (formerly Mt McKinley), where, using skis fitted with climbing skins, and crampons, and avoiding fixed ropes as per the values underpinning his project, he set an up-down time of 11 hours and 48 minutes, carving more than five hours off the previous best. Then, in December, he smashed the record on the Western Hemisphere’s highest peak, Argentina’s Aconcagua (6 962m).

The high-altitude 24km he ran to Plaza de Mules base camp at 4 350m would have wiped out many a talented athlete, but this was merely the precursor to the 40km of slope to the summit. Turning round at the top, he scorched his way back down again at four-hour marathon pace. Another virtuoso performance, another record. Jornet was named National Geographic Adventurer of the Year, and Summits of My Life was right on track… but the project’s undisputed high point was still to come.

To those who have followed Jornet’s career from the beginning, his glittering exploits in speed-mountaineering over the past five years will seem like a natural progression. Versatility has been the runner’s hallmark since he first propelled himself into the public consciousness in 2008, winning and setting a 20-hour course record in the 161km Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB), European trail-running’s flagship event. Within the field of sinewy, trail-hardened runners tackling the route’s punishing 9 000m-aggregate climb, the name of the fresh-faced kid from the Pyrenean mountain village of Cap de Rec in Cerdanya was already being whispered with awe.

He didn’t look back; he rarely has to.

There followed an unrivalled streak of success across the full spectrum of trail running: mammoth, multi-day ultras such as the 800km Transpirenaica crossing of the Pyrenees; revered US spirit-crushers such as Colorado’s Hardrock 100 (a course record for Jornet), the 165-mile (266km) Tahoe Rim Trail in California (ditto) and the Western States 100; shorter trail races such as the Pike’s Peak Marathon and the Zegama-Aizkorri – the ‘Tour de France of trail-running’; vertical kilometre races; Skyrunning world championships; a course record for the GR20 in Corsica (regarded by many as the toughest trail race in Europe). A trail-running trailblazer, his range of success is akin to Usain Bolt dominating every track event up to and including the 10 000m – and then adding the steeplechase just for kicks.

Marino Giacometti, who first met Jornet when the then-shy 16-year-old approached him at a race, believes it’s this versatility that sets him apart. “There have been great trail runners before, of course,” he says. “Mountain runners, too. But no one with such a range. Skyrunning, ski mountaineering, the traditional long-distance trails – Kilian has been able to do all these disciplines, and at the very best level. He’s like a skier who is able to win in the slalom, the downhill, everything. He is unique.”

It’s a measure of his stature that even before the recent profile-boosting assault on those totemic peaks, Jornet was as close as a trail runner gets to being mainstream. He has more than a million followers on Instagram and Facebook; sponsorship deals with Salomon, Suunto, Petzl and Mercedes-Benz; an autobiography, Run or Die, that was shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award; and a regular output of videos that are devoured by his YouTube fans in their hundreds of thousands.

SOLE TO SOUL

Yet humility runs through him as surely as showmanship does through Bolt. You’re no more likely to see Jornet posing for a tongue-out, devil-prong selfie atop a mountain than you are to see him and partner Emelie Forsberg, a fellow ultra-running champion, hanging around red-carpet events. “Kilian is able to speak publicly and do presentations or sponsor’s events or whatever,” says Giacometti. “But in truth he’d prefer not to be involved in such things. I often think the reason why he loves the mountains so much is because they give him the chance to be alone.”

Jornet’s Summits of My Life project was built on a series of core values. Some may sound a little too ‘eco-spiritual’ to some (“We’ll learn to coexist with the real world, the world of rocks, of plants and ice”), but in their entirety they chime with the anti-consumerist drive towards a meaningful reconnection with nature. “We have to learn to live with less,” the values conclude. Jornet’s fast and light approach to his work on the mountains seems a neat embodiment of this.

Patrick Leick, a senior project manager at Salomon, spent two years working with Jornet honing the specialist equipment he would wear for Everest. He describes him as thoughtful, focused and unfailingly approachable. “I first met Kilian before he won the UTMB for the first time. He’s not changed a bit – still quiet and modest.”

When RW spoke to Jornet in the wake of his second unsuccessful attempt to set a FKT on Everest last summer (poor weather conditions, and good judgement, put paid to that) it was hard work prising the figure of his highest recorded VO2 max out of him. It is a scarcely fathomable 92 ml/kg/min (elite runners range from 70-85 ml/kg/min). What also came through was the strong streak of the runner-philosopher in him, in the mould of author and runner Haruki Murakami. Thoughtful, placid, utterly grounded. “Life is not something to be preserved or protected,” he says. “It is to be explored and lived to the full.”

From anyone else it might sound like a bumper-sticker platitude, but Jornet’s musings about mortality have been forged by deep personal tragedy. Summits of My Life started out by costing a life: French ski mountaineer Stephane Brosse, 40, was killed in June 2012 as he and Jornet attempted a speed crossing of the Mont Blanc massif from Les Contamines in France to Champex in Switzerland. Jornet was just a metre away when a snow cornice on the Aiguille d’Argentiere collapsed, plummeting his friend and mentor 600m to his death. Now, whenever Jornet is in the mountains, Brosse is never far from his mind. “Stephane’s death has made me more cautious about the conditions of nature and how fast they can change,” says Jornet. “We can control ourselves, and our technique, but it takes time – a lot of time – to really know the mountains.”

Brosse, Jornet candidly admits, was his idol. Among the many things he credits the older man for is introducing him to the concept of operating in the mountains in a lightweight manner. Another mentor, Swiss speedclimber Ueli Steck, was also instrumental in Jornet’s transformative achievements over the past five years. A formidable pair – the world’s fastest mountain climber (Steck set the 2:22 record for ascending the north face of the Eiger) and the world’s fastest mountain runner – they tackled various peaks together, including a 10-hour ascent of the Eiger from Grindelwald in 2015.

“We’re not pioneers but I think we are bold,” Steck told RW last year, brimming with praise for Jornet, and pride at what the Catalan was attempting in the unforgiving crucible of Everest. “We are testing what is possible – what can I do with my body, where is my limit? I believe it’s the wrong approach to just compare yourself to others and try to beat them. It needs to be a more personal thing: to push yourself as far as you can.” Words that will strike a chord with all runners, whether we’re tackling mountain ascents or our local parkrun.

Tragically, seven months later, Steck too was dead, falling 1 000m while climbing the Himalayan peak of Mount Nuptse. Jornet was deeply affected by the tragedy – but there was never any question of him abandoning his record attempt scheduled for a few weeks later. “In a way it’s better to die in the mountains than, say, a car accident,” Jornet once reflected. “But I think it’s never good to die.”

BLURRING THE LINES

Some may question how much of the Everest – and other – ascent(s) can really be classed as running, but they illustrate a narrowing gap between trail running and mountain climbing. Jornet’s influence on this merging of the horizontal and the vertical is unquestionable, but it is not a movement he is driving single-handedly. The tradition of running up and down mountains is well established: the Ben Nevis race in Scotland dates back to 1898; the Pikes Peak Marathon, in Colorado, has been delighting masochists since 1956 (Jornet won it at a canter in 2012).

What has changed is the level of organisation, the GPS-enabled trend towards setting and chasing FKTs, and the sheer scale of the mountains. No one is going to ‘run up’ the north face of the Eiger, such is the technical difficulty of the vast concave slab. But, as Jornet recognised, many of the biggest lumps on the planet aren’t in fact overly technical. Everest, apparently, being a case in point.

Giacometti’s Skyrunning movement has been gathering momentum since the early 1990s and there are now more than 200 races worldwide, with around 50 000 runners. Defined as mountain running above 2 000m, it’s essentially Alpinism without the clutter. It was made for Jornet, and Jornet for it.

Bergen-based Briton Jon Albon, Obstacle Course Racing world champ 2014-2016, is another athlete lured away from his bread and butter by the mountains. Last year he won the Skyracing Extreme World Series, a set of races devised by Jornet himself. But Albon’s Skyrunning career didn’t start so well. In his first Skyrace, in Limone, Italy, in 2014, he found himself up against Jornet. “I didn’t really see him, to be honest,” says Albon. “He was 15 minutes ahead. That sums up how most people feel when they race him.” Albon was not surprised that the Summits of My Life project was born – nor where it culminated.

“There was a point when people thought it was stupid to run up and down any mountain, let alone the biggest in the world. If there was ever anyone going to do something like this on Everest, it was Kilian.”

As with so much of what he does, Jornet’s achievements on Everest looked, if not effortless, then certainly inevitable. But there was apprehension in his camp for this one. Leick was edgy and didn’t sleep for nearly two days around the attempt. Giacometti likewise. Being fast and nimble in the mountains can have its advantages; you’re not exposed to extreme weather changes in the way that those tied to spending multiple days ascending a mountain are. The avalanche risk is lower, too, given the relative brevity of your time in situ. But fast and unsupported does equate to more risk overall – and how Jornet was going to react to extreme altitude was an unsettling unknown.

“On Everest, the mountain is boss, the weather is boss, you are not the boss,” says Giacometti. “And I was anxious for Kilian’s performance over 8 000m. It’s not a question only of VO2 max, for instance; beyond 5 000m your VO2 reduces by nearly half. Different people have a different reaction over 8 000m. I said to Kilian, ‘please return’!”

Jornet did so – an outcome he credits in large measure to what he has learned by running. He speaks of the indefatigability that ultra-running pounds into you, the ability to go to the well and drain it – then run for another 20 hours. So, too, the instinct to keep moving at a brisk pace, and the precise understanding of your body’s complex balance between nutrition and performance. “My experience was worth so much on Everest,” says Jornet. “Those longer races, the ultras, the 100-plus-mile races. These teach you to fight when you’re tired, to never give in.”

Preparation was a cornerstone of Summits of My Life. The Spaniard’s laid-back demeanour belies a furious fastidiousness, and if you respect the mountain, then it follows that you must also prepare for it. Ahead of his Matterhorn attempt, Jornet tested out the route eight times and lay in wait for the optimum conditions, timing his afternoon departure to the minute to ensure he’d encounter the minimum possible ice. He planned Everest for two years. When the 2016 attempt failed owing to poor conditions, he adjusted the plan, coming out early and spending two weeks training on another 8 000m mountain, Cho Oyu. He made repeated recces, moving between 6 400m and 8 400m. Great for his Instagram feed, even better for his body. The Jornet camp called it ‘express acclimatisation’.

GAME CHANGING

The principle of a single push is a good one – with one enormous caveat: that you have the mental toughness and fitness to carry it off. The de rigueur multi-day ascents of a mountain like Everest are predicated on overnight rest stops at various camps. Yet sleeping at altitude is nigh on impossible. The result is accumulated weariness, magnified by the thin air. The mountain is littered with the bodies of those who stopped for a quick rest – almost falling asleep mid-stride – and never woke up. In such brutal conditions, your heart rate slows and exposure overcomes you.

One of the allies Jornet made on Everest was American Adrian Ballinger, a mountaineer who has 10 Everest seasons under his belt. The two men summited – both without oxygen – on the same day, Ballinger having taken a more conventional multi-day approach. And they shared a tent back at Advanced Base Camp, where Jornet willingly signed autographs despite having been on his feet for more than 30 hours.

Jornet’s exploits are already making the likes of Ballinger reconsider their strategies. “We’re starting to play around with this,” he says. “Sleeping at high altitude has its challenges and dangers. Going up and down so quickly, as Kilian did – the style requires a certain element of confidence that your fitness is going to facilitate this. Kilian really played right on the edge of that, and he told me he ended up having to nap up high briefly, crawling under a boulder. That is the risk.” He adds: “I don’t think he was ever in danger, though. Kilian’s stamina is absolutely incredible.”

Even as Jornet chips away at mountaineering conventions, there’s barely a whisper of discontent from this hard-bitten community. Ballinger and climbing partner Cory Richards say they know of no-one with ill feelings towards him. “As far as we can see, people are just stoked about how fast Kilian moves in the mountains,” says Richards. “And a big part of that is Kilian himself. Shy, humble, friendly.”

It’s certainly hard to paint Jornet as an imposter in the Himalayas – and there’s little shortage of those, season to season: high-net-worth, low-skilled clients with as much oxygen and support as they can buy being, in the words of detractors, ‘dragged to the top’. In so many ways, Jornet is their antithesis.

In fact, so entwined with the mountains is Jornet that six days after reaching the summit of Everest, he was once again gazing up with intent. It wasn’t in the original plan; but as he rested up at ABC, word got out that he might be having another shot at the summit. For a FKT from ABC to the top and back? For more glory? It’s a safe bet it was more probably just for the sheer joy of it.

He made it, of course: a single 17-hour push from ABC to the summit on May 27, in the process becoming the first non-sherpa to summit Everest twice in a week without oxygen. “That’s what really hit Cory and me,” says Ballinger. “I’ve done two summits in a week with oxygen, and I was devastated – wiped out. I did it once, without, this year, and couldn’t even begin to picture doing it again.”

NEW HEIGHTS

Most observers agree the legacy of the Summits of My Life project will be wide-reaching. In the Alps, mountaineers are already beginning to look at ways of tackling peaks faster and lighter. “I think Kilian’s performances have started to revolutionise the world of high mountaineering,” says Leick. “I predict the same evolution of high-mountaineering footwear as we’ve seen in trail running.”

As for Jornet, Ballinger believes he has barely scratched the surface of what he can do, and will go on to break all sorts of records. “But more importantly, he’s started the whole movement towards these FKT times,” says Ballinger. “He’s going to push a whole generation of other athletes.” It’s already happening. In the same way as with a Bannister, a Bolt or a Steck, or anyone who raises a bar by a significant margin, others find themselves growing within those expanded parameters. Just a few months after Jornet set his 12:49 record on Aconcagua, emerging mountain-running sensation Karl Egloff lowered the time to 11:52. “It’s like Kilian has shown the world what is possible,” says Richards.

After Everest, Jornet returned to the Alps to begin his preparation for this summer’s UTMB. But it’s a fair bet that there’s only so long he’ll be content to run around massifs rather than up them, now that he has so dramatically expanded his horizons. “The project is finished,” says Jornet. “It’s cool because it has been a long adventure, five years meeting a lot of people, learning from every experience, and growing as an athlete and a person.” He pauses. “But, of course, there are always dreams. The trouble is, you climb a summit; and from the top, all you can see are other summits.”

READ MORE ON: motivation travel